You should not, of course, simply accept all the ‘facts’ that are presented to you. Be particularly wary when presented with scientific and statistical arguments, and complex computer models.

Statistics can be particularly misleading. Follow this link to access detailed advice about the use and mis-use of data.

Science

It is all too easy to frighten people with ‘science’. 76 per cent of one group of adults, presented with a number of true facts about the chemical di-hydrogen monoxide, concluded that Government should regulate its use. The other 24 per cent presumably knew that the chemical’s other name is ‘water’.

There are many scientific ‘facts'. But research scientists work by publishing their theories and conclusions so that others can test them. Slowly, over time, it becomes clear that what scientists are saying is very likely true, and should be acted upon. But you can always tell good scientists by the way in which they acknowledge any remaining uncertainties, make assumptions explicit, distinguish between what is true and what is speculative, and present options.

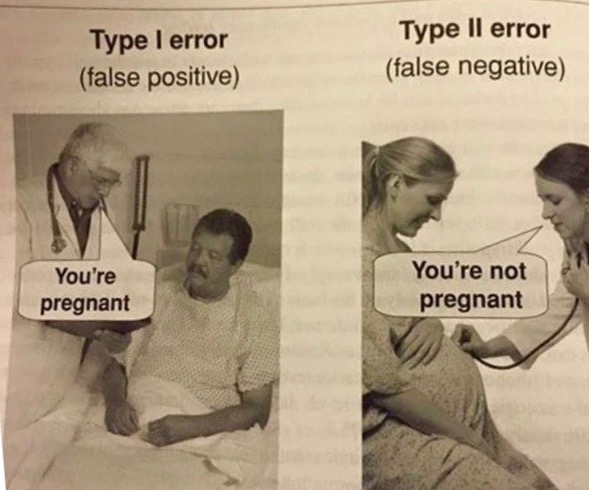

Scientists, medics and economists will often report the likelihood of 'Type 1' and 'Type 2' errors - or false positives and false negatives. A test for cancer will, for instance, result in a number of people being told that they may have the disease - when they haven't - and others being told that they appear not to have the disease - when they do. I prefer to avoid such jargon, but this cartoon neatly explains the difference, if you need to remember it:

Models

You should also beware relying too heavily on cost benefit analyses and other complex models. They can illuminate difficult decisions, but their results depend heavily on the assumptions built into the model, many of which may be well hidden in various formulae and code. Models are therefore no substitute for careful analysis.

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic has shown the value of computer simulations - but also their limitations. Decision makers need to understand the assumptions that are built into the models, and the uncertainties in the predictions. Crucially, the modelers also need to be able to explain how changes in assumptions lead to changes in predictions, not least because decision makers need to be able to explain their decisions to those to whom they are accountable.

Judges in particular, in Judicial Review proceedings, will take no notice of black box models whose workings cannot be explained. As John Kay noted in his FT column, commenting on the decision to proceed with a third Heathrow runway:

Roskill made a pioneering and widely praised attempt to use cost benefit analysis to define the relevant issues. By the time the Airports Commission reported in 2015, this modelling exercise had morphed into a monster, a black box with trailing wires whose processes no one could understand, and which offered endless numbers but no insight. Such over-specified and convoluted models are used as rationalisations for decisions that have in reality been taken on quite different grounds.

The power of modern computing, far from facilitating good decision making, gets in the way. Consultants are dispatched to find supportive numbers. This happened with HS2, the proposed high-speed link to Birmingham, and for years a policy in search of a justification. Competing cost benefit analyses yield the recommendations their sponsors want to hear. We have policy based evidence, not evidence based policy.

Other Pressures

Moving beyond science, models and statistics, you must remember that it is unfortunately in the nature of our society that most correspondents, and most of the people that we meet, will present a one-sided view of an issue, drawing attention to all the relevant facts and arguments which support their case but failing, either deliberately or through sheer conviction, to take account of inconvenient facts or opposing arguments. But as you gain experience, you will quickly learn to detect the pure advocate or bullshitter.

Take care, therefore, not to be too trusting and bear in mind the famous warning that ‘He would say that, wouldn’t he!’ No one who is applying for a grant will tell you that they will in fact go ahead even if they do not get it, and no businessperson will tell you that the principal purpose of their latest acquisition is to build market power. Similarly, most people are reluctant to admit their errors, and their reluctance will be in proportion to the seriousness of their error. Therefore, if you are questioning the propriety of someone’s behaviour, be cautious about attaching significant weight to the views of the person being questioned. Find out the facts and let them speak for themselves.

The same applies, but less strongly, to professional advisers. Lawyers, accountants and merchant bankers are employed by their clients to persuade you to do certain things. They will usually tell you the truth, but seldom the whole truth. They will also sometimes imply, and indeed believe, that their opinion (e.g. about the viability of a project or the prospects of a company) is a fact. If your instinct is to the contrary, then rely upon that instinct, at least to the extent of probing further.