Ministers, assisted by their civil servants, are primarily accountable to Parliament, not to the media or anyone else. Ministers' accountability takes two forms. First, Parliament can question and debate both policies and behaviour. Second, it exercises close control over Government expenditure.

Separately, those civil servants who have been appointed as Accounting Officers are directly accountable to Parliament for the expenditure of their department or agency. And many senior officials appear with or on behalf of their Minsters when being questioned by Select Committees.

The Parliamentary Timetable

A new Parliament begins after every General Election.

A new Parliamentary Session begins with the Queen’s Speech (usually in May each year) and, in the absence of an election, runs through to the following April, with a big gap for the Summer recess. Bills cannot normally be carried over from one session to another but there are a growing number of exceptions to this rule, about which you can get advice from your Parliamentary Branch.

The Parliamentary day usually begins, with prayers, at 2.30 on Mondays, 11.30 on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, and 9.30 on Thursday and Fridays. Officials are not allowed into ‘the box’ near their Ministers until five minutes later when (except on Fridays) First in Order Oral Questions begin (usually abbreviated to First Order PQs or Oral PQs). These normally last one hour, but only 30 minutes on a Wednesday - when they are followed by 30 minutes of Questions to the Prime Minister.

Next come Urgent Questions. These are nowadays allowed quite often – on average around once a week - and typically last around 40 minutes. These are then followed by Statements. There may be none but there is usually one, and often more then one, and each can last for up to forty-five minutes or an hour, much to the frustration of Ministers and their officials waiting for subsequent business. The first Statement on a Thursday is usually the Business Statement by the Leader of the House, who needs briefing on Early Day Motions.

Next (briefly) come applications to the Speaker for Standing Order 20 (i.e. Emergency) Debates. Applications are rarely accepted but, if they are, they take place later that day or next day. And then there might be a Ten Minute Rule Bill – an opportunity for an MP to speak for ten minutes on a topic which they regard as important. Another Member (but not a Minister) might reply, again for up to ten minutes.

And then at last we get to debates on Bills, Opposition motions and so on, which run through to a final 30 minute Adjournment Debate.

In parallel with the main chamber, there are frequent Westminster Hall debates on non-contentious business. These sittings actually take place in the Grand Committee Room just off Westminster Hall and are usually held on Tuesdays (am & pm), Wednesdays (am & pm) and Thursdays (afternoon only). There can be considerable variations on the above – especially as Parliament from time to time experiments with different formats and timetables. Your Parliamentary Clerk will keep you right, and will give you the phone number of the police officer at the back of the Speaker’s chair, where Ministers enter the chamber and where officials enter the box. He or she is unfailingly helpful and will in particular be able to tell you the time before which your business is unlikely to start, so allowing you to maximise your time in a nearby coffee bar or, if in the middle of a panic, in your office.

Parliamentary Questions

It cannot be stressed too strongly that Ministers and officials are under a duty to be both open and absolutely honest when answering questions from parliamentarians, whether at question time, in debate or in correspondence. Put simply, MPs are entitled to straight answers to straight questions.

Written Questions are those where both the question and answer are written, and they are part of the process by which MPs gather information from the Government. They tend not to be used for political point scoring because they do not usually receive much media attention. Therefore, unless the question is obviously antagonistic, Ministers will usually reject draft answers which are deliberately cagey. In general, it is best to aim for accuracy and brevity in both the draft reply and the background note. And if the reply is likely to fill more than two columns of Hansard, you might suggest that the answer is that ‘I will write to the Hon. Member and will place a copy of my letter in the Library’.

On the other hand, Parliament is a political arena and indeed some Parliamentary ‘questions’ – and especially Oral Questions – in substance amount to little more than political point-scoring. Therefore, as noted above, it is perfectly proper for a civil servant to prepare a draft letter, Statement or Parliamentary Answer which praises the Government’s policies, and it is perfectly proper for our drafts to omit facts and arguments which might cast doubt on the appropriateness of those policies. But even in these circumstances, any factual element to the answer has to be accurate and the answer, when read as a whole, must not mislead the reader.

The more pedantic of my colleagues will wish me to point out that many Oral Questions are actually written, in the sense that they appear on the Order Paper and are not repeated before the Minister rises to reply to them on the floor of the House. But the answers are oral, as are Supplementary Questions and their answers. There are therefore two stages to preparing answers to these Oral Questions. First there is the easy bit, drafting a short answer to the Question as tabled. Second, and much harder, you have to anticipate what lies behind the Question by suggesting key points to make and answers to possible Supplementaries.

There are also Topical Oral Questions, where the MP can ask about any topical issue which is within the Department's responsibilities. There needs to be prior liaison between the Minister's offices, the Parliamentary Private Secretaries, the Press Office and officials in order to identify topics which may come up, and briefing then needs to be provided.

Prime Minister’s Questions are rather similar to Topical Questions in that they are almost always open questions about the PM’s engagements, so allowing the questioner to ask Supplementaries about any issue which is causing controversy. You should therefore offer briefing (via Parliamentary Branch) if your subject has become newsworthy, providing only one or two key points to make, so that the Prime Minister can forcefully and succinctly deal with any attack. It can be helpful to divide the briefing into three sections: the Accusation, the Facts - which must include any uncomfortable facts which may be quoted in critical questioning - and the Line to Take. Do not provide politicised material. This will be done by your Special Adviser and staff in Number 10. And you should provide only as much defensive material as is necessary to keep the Prime Minister from making a serious mistake. No. 10 do not expect perfect briefing, for time is too short, but they will complain - as I once saw - if 'the material was too lengthy, concentrating on detail inappropriate to Prime Minister's Questions, and therefore failing to make the main points effectively'.

When dealing with all Parliamentary Questions (PQs) you should remember that the Ministerial Code makes it very clear that Ministers must not knowingly mislead Parliament or the public, and should be as open as possible with Parliament and the public, withholding information only when disclosure would not be in the public interest, which should be decided in accordance with any relevant statute law and current open government law and practice. Ministers also have a duty to give Parliament and the public as full information as possible about the policies, decisions and actions of the Government. It is our responsibility to help Ministers fulfill these obligations, and information should never be omitted from a draft reply simply because its disclosure could lead to political embarrassment or administrative inconvenience. But of course potential problems should be highlighted when the draft reply is submitted to the Minister.

It is different, of course, if the requested information is classified, or has been given in personal or business confidence. Ministers should be advised to refuse to answer any question which calls for such information, on the grounds of commercial confidentiality etc. An MP will sometimes, inadvertently or deliberately, show interest in an issue, the full exposure of which would be seriously damaging to the nation or to one or more individuals or businesses. In these circumstances it is sometimes possible for a Minister to meet the MP in question and explain the need for discretion – for the time being at least. If necessary, there can be consultation on ‘Privy Council terms’ between a Cabinet Minister and a senior member of the Opposition.

It can be interesting to debate whether honesty is required in certain hypothetical situations. But these circumstances are very unlikely to apply to any of us at any time in our career. In short, therefore, Ministers must always be given answers which are neither dishonest nor misleading. It is not clever to do something else; it is unprofessional and wrong.

Urgent Questions

Your job is to prepare clear briefing for the Speaker so that he or she can decide whether the Question should be allowed. The briefing usually has to be prepared in a great hurry. Urgent Questions can be tabled only an hour or two before the beginning of the Parliamentary day, and the Speaker needs to be briefed only minutes later, so time can get ridiculously short. It is vital that you are contactable if there is any chance of an Urgent Question being asked in your area.

It follows that the briefing should be very short and essentially factual, containing (if appropriate) enough information to demonstrate that the matter has already been well aired, or that the matter is not urgent, or that it is not the direct responsibility of the Government. Indeed, if it looks as though an Urgent Question might well be allowed, Ministers will often volunteer a Statement (see below) so as to avoid appearing to be forced into answering to the House.

You will know within a few minutes whether the question has been allowed. If it has, then you will need to move very quickly to prepare your Minister for the c.40 minute session beginning after Oral PQs.

Standing Order 20 (Emergency) Debates

Your role is to provide briefing so that the Speaker can decide whether to hear the application for an emergency debate, and if the application is heard, whether to accept the request. The MP’s application can take up to only three minutes. If the application is successful, you will have to prepare for a full-scale debate either that evening or (you hope) the next day.

Early Day Motions

These statements of opinion signed by MPs are seldom debated, but you will need to brief the Leader of the House on them. And if the Opposition Front Bench table an EDM contrary to Government policy, you will quickly have to draft an amendment.

Ministerial Statements

Statements are normally made about major issues and developments which are likely to attract much attention both in Parliament and in the media. They are major events and take high priority.

The word ‘Statement’ is a little misleading in that the Statement itself (which is read out by the Minister – and almost always a Cabinet Minister) is always followed by a grilling by interested MPs from both sides of the House. The Statement itself therefore needs to be drafted with great care so as to ensure that it is clear, informative and concise, and contains no hostages to fortune. The Minister’s Private Office will clear the draft with Number 10 and a copy of the Statement is then usually given to the Opposition 15-30 minutes before it is due to be made. A Lords Minister will usually repeat the Statement in the House of Lords. As well as drafting the Statement, you will need to prepare thorough briefing for the Supplementary Questions in both houses.

By the way, if your Minister wants or needs to make an announcement that does not justify a Statement, you should consult your Parliamentary Branch about tabling a Written Ministerial Statement. Copies are then made available next day in the Vote Office, and the Statement also appears in Hansard.

Adjournment Debates

These daily debates allow MPs to draw attention to constituency and other matters. It is often the case that there are no other MPs in the Chamber, and the Minister will usually wish to respond sympathetically to what is said. You will need to provide a closing speech (about 10 minutes’ worth) which the Minister will amend or embroider once he or she has heard the opening speech, and you will need to supply background briefing.

At least one official will need to be in ‘the box’, and if you miss your last train then the Private Office will arrange to get you home. However, if the debate is likely to be in the small hours, and the Minister is familiar with the subject, you might be let off!

Timed adjournment debates also take place on the last day of each Parliamentary term. Eight topics are selected by ballot at least two days beforehand and the debates are otherwise broadly similar to the daily debates.

House of Lords Business

Procedures in the House of Lords are broadly similar to those in the Commons, but they vary considerably in matters of detail. For instance, I can never remember the difference between starred and unstarred questions. So don’t assume anything but check with the Private Secretary to the Minister concerned, and double-check with Parliamentary Branch. If the two of them agree then you have probably been given accurate information. If they disagree, then get them to sort it out!

Generally, of course, the Lords are much more civilised than the Commons, and you get much more notice of most business. But do not underestimate the Lords. Many of them are real experts, and many of them are very experienced politicians. Also government spokesmen and women in the Lords have wider portfolios than their counterparts in the Commons. These two factors together mean that your drafting and briefing has to be of very high quality.

Bills and Standing Committees

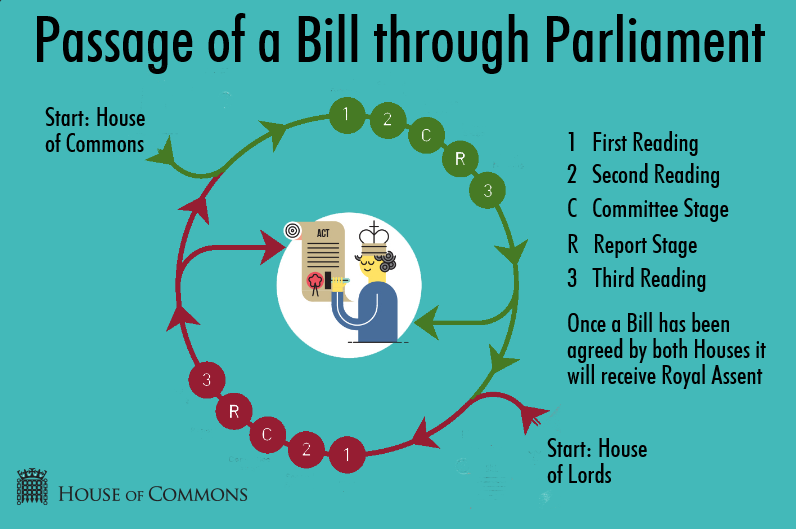

Bills (i.e. draft legislation) go through a number of stages, summarised in this chart:

In more detail, the key stages are as follows.

- Your Minister gets policy approval and drafting authority from Cabinet colleagues. This means that the Parliamentary Draughtsman can start work, having been instructed by your departmental solicitor who is in turn instructed by you.

- Your Minister then gains collective agreement that the Bill will form part of the legislative programme and (unless it is relatively minor and uncontroversial) it is announced in the Queen’s Speech in November.

- There then follows Introduction and First Reading (usually a formality).

- Second Reading then triggers a major debate on the merits of the Bill.

- Committee Stage follows, in which a General Committee - usually a Public Bill Committee - examines the legislation in great detail. (Committees of the Whole House are used for the Committee Stage of certain major Bills, particularly on constitutional matters.)

- Next comes Report Stage, in which the Bill as amended in Committee is reported back to the Whole House, and again debated, and possibly further amended.

- Finally, for the moment at least, there comes Third Reading, following which the Bill is approved for onward transmission to the Lords (if it began in the Commons) or to the Commons (if it began in the Lords).

Then the whole process is repeated in the other House. If the Bill has not been amended in the other House then it goes on to the Monarch for Royal Assent, whereupon it becomes an Act of Parliament and part of the UK's body of primary legislation. If it has been amended then it ping-pongs between the two Houses until they agree on a text, whereupon it then goes forward for Royal Assent. It is important to note that the legislation often, indeed usually, does not come into force straight away. The commencement date(s) of the various provisions in the Act may be found either in the Act itself or else in Orders which are made under the Act - see further below.

It will be clear from the above that taking a Bill through Parliament is a major and high profile task, always entrusted to a separate Bill Team. If you get anywhere near this process, you must start by reading the detailed information and instructions which your department will make available to you. You should also go to see, and listen carefully to advice from, the Cabinet Secretariat and your Parliamentary Clerk. And take care that you have enough resources, in the form of people and IT, photocopiers etc. The workload can be huge and urgent, especially during Committee Stage.

Secondary Legislation

You are much more likely to get involved in drafting secondary or delegated legislation - that is Statutory Instruments (usually Orders and Regulations) that are made under the authority of previously enacted primary legislation. There are two types of Statutory Instrument, and the form that you need to use will be specified in the associated primary legislation:

- Affirmative instruments: Both Houses of Parliament must expressly approve them

- Negative instruments: become law without a debate or a vote but may be annulled by a resolution of either House of Parliament

In both cases, Parliament's room for manoeuvre is limited. Parliament can accept or reject an SI but cannot amend it.

There is much good advice about avoiding over-burdensome regulation in the Getting the Balance Right section of the Understanding Regulation website.

Other Powers - The Royal Prerogative & Orders in Council

For completeness, you need to be aware that not all legislation etc. has to be approved by Parliament.

The Royal Prerogative enables Ministers, among many other things, to deploy the armed forces, make and unmake international treaties and to grant honours. Government Ministers exercise the majority of the prerogative powers either in their own right or through the advice they provide to the Queen which she is bound constitutionally to follow. The three fundamental principles of the prerogative are:

- The supremacy of statute law. Where there is a conflict between the prerogative and statute, statute prevails. Statute law cannot be altered by use of the prerogative;

- Use of the prerogative remains subject to the common law duties of fairness and reason. It is therefore possible to use judicial review to challenge the use of the prerogative;

- While the prerogative can be abolished or abrogated by statute, it can never be broadened. However, Parliament could create powers by statute that are similar to prerogative powers in their nature.

Orders in Council are made by The Queen acting on the advice of the Privy Council and are approved in person by the monarch. Some, like those that transfer functions between Ministers of the Crown, are made using powers conferred by an Act of Parliament. Others, like those which make appointments to the civil service, are made by virtue of the Royal Prerogative. Although Orders in Council must be formally approved in person by the monarch, they are drafted and their substance is controlled by the government.

Select and Grand Committees

Select Committees oversee the work of individual departments, and often call officials to give evidence. There are also some specialised Select Committees, such as the Public Accounts Committee and the European Scrutiny Committee.

The Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish Grand Committees operate along similar lines except that, interestingly, they frequently hold meetings in Scotland etc.

Select Committees are appointed for a whole Parliament and so become experts on their subject matter. Party differences are usually (but not always) much less important than, for instance, in main chamber business, and there is usually a good deal of consensus. Select Committees therefore deserve considerable respect.

Having decided what subjects it will look at, a Committee will generally call for written evidence from outsiders, and a position paper from the department. It will then take written and oral evidence before preparing a report for the Whole House. These are important documents to which Ministers are expected to respond in writing.

If you are asked to prepare evidence for, or brief a colleague who is to appear, or appear yourself, before a Select Committee then you should carefully read all the guidance that is available from your Finance Division and your Parliamentary Branch. If you or a fellow official is giving evidence then your Minister will require you to follow the Osmotherly Rules which are included in a document entitled Giving Evidence to Select Committees - Guidance for Civil Servants. Put shortly, you may describe and explain the reasons which caused Ministers to adopt existing policies but you should not give information which undermines collective responsibility or get into a discussion about alternative policies. In particular, you are not allowed to divulge:

- Advice given to Ministers by officials;

- Information about interdepartmental exchanges on policy issues, the level at which decisions were taken, or the manner in which Ministers consulted their colleagues;

- The private affairs of individuals, including constituents;

- Sensitive commercial or economic information, and

- Information about negotiations with other governments or bodies such as the European Commission

The Clerk to the Committee will usually give you a good idea of what is needed (if you are preparing a memorandum) and will try to predict the likely line of questioning (if you are appearing in person). The key things to remember are:

- Be brief;

- Be as helpful as you possibly can;

- Be truthful and accurate, and say if you do not know the answer. (Correct any mistakes or misleading answers as soon as possible afterwards. This is often necessary, and Committees understand that mistakes are made under pressure)

- Be tactful about having greater knowledge than the committee (if you do!);

- Maintain self-control, even under provocation;

- Do not tell jokes;

- You appear on behalf of your Minister who must agree your proposed response;

- Your Minster is responsible for what information is given to the committee and for defending his or her decision as necessary;

- You may not publish written evidence – it belongs to the Committee;

- You may publish your response to a Committee report, but only after it has been received by the Committee.

Petitions

There is a Petitions Committee which looks at e-petitions submitted online by members of the public. These have sharply raised the impact and hence the political importance of petitioning. The committee seeks observations from departments before deciding which e-petitions should be debated in Parliament. But it is worth noting that e-petitions do not replace the ancient paper petition process. Paper petitions can be presented with only a single signature and can be useful in drawing attention to local or small scale concerns

Parliamentary Control of Expenditure

Students of history will recall that the Commons’ control over the Crown, and subsequently over the Executive, was exercised through control over expenditure. This control is still jealously safeguarded by MPs, including through the Public Accounts Committee, to which ‘Accounting Officers’ (usually Permanent Secretaries) are directly accountable for the propriety and value for money of the department’s expenditure. Civil servants may therefore only spend money if they comply with statutory constraints and detailed rules which are not found in the private sector and which can sometimes seem irksome and frustrating. In particular, it is always necessary to ensure that expenditure is permitted by, and within the limits set by, both the Treasury and Finance Division. It is absolutely wrong, and a serious disciplinary offence, to break or circumvent these expenditure controls.

In addition, MPs are understandably concerned to ensure that both Ministers and civil servants do not waste or profit from the taxes that are extracted from their constituents – many of whom are not well off and who would rightly object if civil servants either wasted their money or used it to fund an extravagant lifestyle, whether on or off duty. Put bluntly, those who want to be generously paid, or to operate a generous expense account, should not become civil servants.

The Public Accounts Committee, in particular, is quite properly intolerant of wasteful expenditure, and of decisions which cannot be supported by careful evaluation and comparison. The committee deliberates with the benefit of hindsight, and can therefore seem intolerant of risk-taking, and of the need to negotiate in uncertain conditions and against tight deadlines. The correct response is not to become risk-averse, but rather to ensure that the reasons for important decisions are properly documented, and supported by appropriate professional advice. With a little planning, this can be done even if the decision in question needs to be taken against a very tight deadline. Do not be surprised if a failure to take these elementary precautions is regarded with considerable suspicion by both the PAC and other observers.

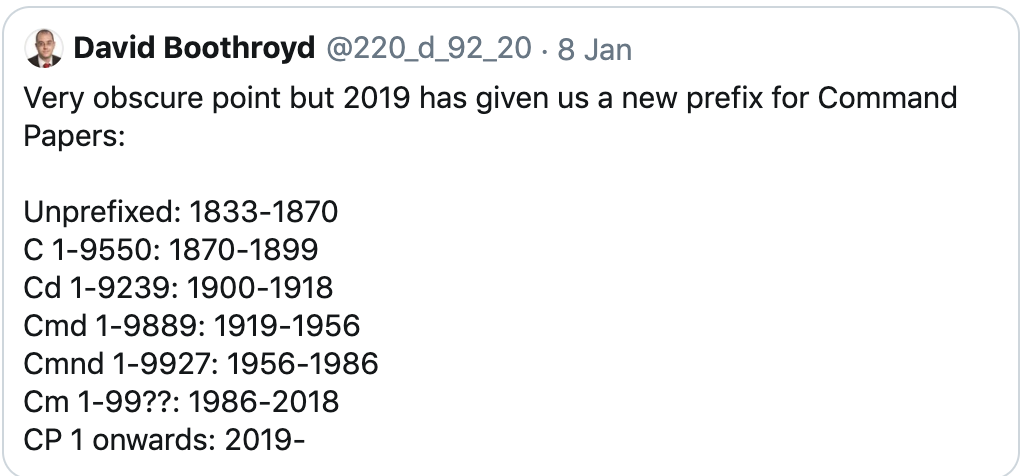

Command Papers

The most important government publications are laid before Parliament "by Command of Her Majesty". Their numbering is confusing but this tweet is very helpful:

By the way ...

The Westminster Parliament may be 'the mother of ' many others, but it is not the oldest in the world. Iceland's Althingi was established in 930 and the Isle of Man's Tynwald in 979. Ireland's first known Act of Parliament was passed in 1216, still a few year's before England's Parliament was first enrolled in 1229.