This is one of four web pages that contain advice about the evidence gathering and consultation stages of the policy process.

If the subject of your consultation is particularly controversial, or if you are to meet a potentially hostile audience, or hostile media, you should remember the following basic rules:

- Actions speak louder than words. The vast majority of your audience will respond wholly or mainly to the way in which you deliver your message. ‘Organisational body language’ is important. Do you act, write or sound patronising, worried and harassed? Or do you act and sound calm, sympathetic and in control?

- Do not dismiss concerns, however silly you think they sound. If it appears that you do not respect basic human concerns, how can you then be trusted to come up with sensible policies?

- Instead, listen carefully and emphasise your own concern. Then commit to continuing speedy enquiries, taking proper advice and reaching an early sensible conclusion on the best way forward. Stress that the process will be participative and open, and that you will publish any scientific or other expert advice and the assumptions upon which it is based. Remember that the public will trust you much more if you admit to uncertainty, and that the public may well be less concerned about the problem than the media.

- Explain the benefits of your proposed approach. Stress that your reaction to any problem will not be ‘knee-jerk’, and you will not patronise or nanny the public. If regulation might be needed, explain how this will protect the public and why other options would not work. If regulation is likely to be unnecessary, stress that you believe it right that the public should be allowed to make their own assessment of the problem, and the associated costs, risks and benefits, and react as they wish.

- A small but crucial minority in your audience will be opinion formers who will want to understand the underlying issues and will analyse your response very carefully. Get the majority of them to accept your credibility, and respect your openness, and they will sustain you against much unfair comment.

- Do not say that a particular option would be ‘too expensive’. Who are you to say that?

- Do not express concern that action to protect the public would harm industry, for this will reinforce any concern that a risk is being transferred from those who are benefiting from it onto those who are not.

- Membership of advisory groups should be broadly based, and not confined to scientists and other professionals.

- When dealing with risks to health and safety, remember that nothing in this world is entirely ‘safe’. The Government’s job is to ensure that everything is ‘safe enough’.

And don't worry too much. People will adjust.

Many consultations concern choices between outcomes that different factions find unattractive. But you have to make a decision - or at least a recommendation, - despite the fact that you will upset quite a few people. It can help if you bear in mind that that you are dealing with a real world situation, not a static laboratory experiment.

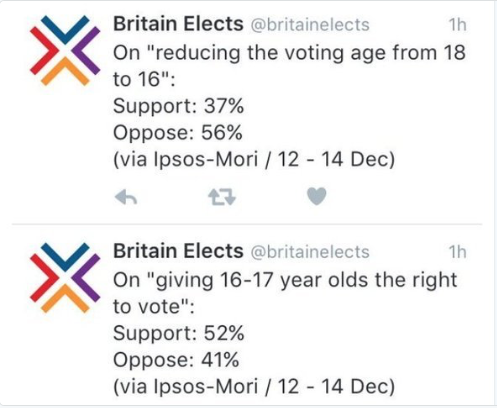

The public's response to questioning, for instance, depends very much upon the way that the question is put. There is a nice 2016 example to the right.

And the public or business community will usually adjust their behaviour to cope with an unwelcome development, or may simply just get used to it. This is why environmental groups, for instance, are so keen to stop certain developments before they become established as precedents. Their response may seem to be out of proportion to the harm done by the proposed development but it might make a great deal of sense in the wider scheme of things. Do not therefore underestimate or patronise such lobby groups.

It is also often the case that widely divergent views are not so far apart as they seem. I was very struck by a 2012 report of two economists' supposedly very different attitudes to austerity. It turned out that they agreed on a great deal, and their policy recommendations weren't so far apart after all.

Indeed, once a policy decision has been implemented, it can be very difficult to tell whether it was correct, and it also becomes very difficult to get back to where you began. Who knows, for instance, whether it was right to give planning permission to certain large developments? But any attempt to knock them down would cause an uproar, from those who live in, work in or supply them, or from those who have simply grown fond of them (Battersea Power Station, for instance). I sometimes wonder what would have happened if our predecessors had known for certain that motor vehicles would end up causing one million deaths a year around the world. So don’t get too upset when a Minister takes an apparently illogical decision. The Great British Public will probably find a way of adjusting to the decision, if not actually circumventing it.