Introduction

This is the first of four pages that contain advice about the evidence-gathering and consultation stages of the policy process.

- You will find general advice on this page.

- Another page considers the need for research and experience.

- A third page contains advice on how to handle particularly controversial consultations.

- And a fourth page gives specific advice for those working in the public sector who often need to follow certain formal processes.

Why Consult?

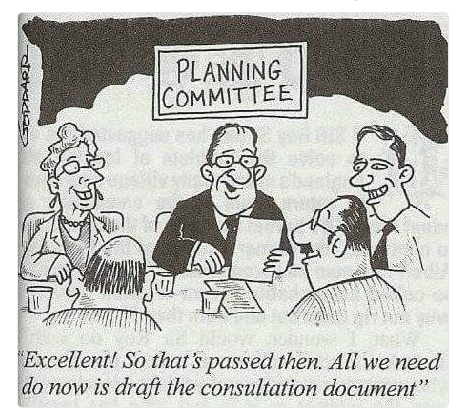

Machiavelli's advice was that princes should consult the many about what they might do, and consult the few about what they are resolved too do. There is much sense in this, and much truth in the following quotation and cartoon.

There is nothing a government hates more than to be well-informed; for it makes the process of arriving at decisions much more complicated and difficult. - John Maynard Keynes

There is nothing a government hates more than to be well-informed; for it makes the process of arriving at decisions much more complicated and difficult. - John Maynard Keynes

Chief Executives and Ministers in a hurry, and their well meaning staff, all too often want to get on and make decisions, and engage in as little real consultation as they can get away with. Modern social media, and the mainstream media that feed on it, also lead to pressurised decision-making. The problem, of course, is that decision-makers and their staff often have unwarranted confidence in their ability to make sensible, speedy decisions, and their ability to change the public's behaviour,. They are also often over-optimistic about what their organisations can achieve. .It can be very difficult to persuade them that research and consultation makes sense - see speaking truth to power. But it can be worth quoting or paraphrasing the military doctrine that 'The first duty of a commander is reconnaissance.' The best laid schemes will certainly go badly awry unless supported by strong and open-minded consultation processes.

Effective Consultation

There used to be a time when the public were much less likely to challenge authority. Big corporations had yet to encounter Ralph Nader and the Consumers Association (now Which?). .And government Ministers could simply tell the public what decisions they had taken. It then became necessary to explain why the decision had been taken, which in turn led Ministers to consult in advance of deciding their policies. Best practice is now to go even further and involve the public and key stakeholders at all stages of the policy process.

There are lots of different ways to do this and you should not simply duplicate what someone else has done before you. In particular, don’t limit yourself to written communications. Discussion groups, large formal meetings, informal meetings with individuals and the Internet all have a part to play. And even when preparing formal written consultation, there are a number of choices. Have a look at the detailed advice that is available on consultation procedures, and also look at a range of previous consultation documents and choose a format which best suits your needs.

Above all, remember that you are in policy-formulation or policy-implementation mode, so there is no need to be defensive. Indeed, you should positively encourage respondents to point out your mistakes and possible pitfalls. Good decision making depends on allowing or even encouraging dissent up to the point when your organisation has taken its decision. If your process is effective, and you take the responses seriously, you will find that you then avoid a very large number of traps that you would not have spotted by yourself.

You should therefore encourage those who seem to be able to take a wider view. Cultivate those who say unexpected things or comment candidly upon their organisation. Such people shine unaccustomed light on issues and can be invaluable contributors to the policy making process. Do not make the mistake of thinking that experts' opinions are necessarily correct. Much science is beyond doubt, but much some softer scientific opinion, such as medicine and economics, may be distinctly flaky. Doctors will tell you that Medical facts (things we know to be true) have a half life of five years, and that Yesterday's heresy is today's orthodoxy and tomorrow's fallacy.

Equally, though, senior professionals can be very reluctant to accept that their 'tried and tested' way of doing things might be wrong - or at least sub-optimal. It took far too long, for instance, for convoys to be introduced in the First World War, because of opposition from the Admiralty. There were many reasons for this opposition, including an unwillingness to accept that the arguments of 'amateurs' might be soundly based. And also, in his book On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, Norman Dixon suggested that the hostility towards convoys in the naval establishment were in part caused by a (sub-conscious) perception of convoys as effeminating, due to warships having to care for civilian merchant ships. Convoy duty also exposed the escorting warships to the sometimes hazardous conditions of the North Atlantic, with only rare occurrences of visible achievement (i.e. fending off a submarine assault).

It is always tempting, and sometimes sensible, to accept the consensus view of numerous experts when trying to predict future behaviour. But a consensus view can sometimes be little more than a best guess - somewhere between upper and lower bounds of expert and/or model's predictions. So you may need to think hard about predictions that lie somewhat outside the consensus. What if that upper bound prediction turns out to be close to what happen? Will you be prepared, or will you be naught napping because you relied too much on the consensus?

(This might have been a problem in the early months of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic when scientists' consensus view (arrived at in the SAGE advisory group) may have been too optimistic that the virus might not be as serious a problem as it turned out to be.)

Experts May Sound Uncertain

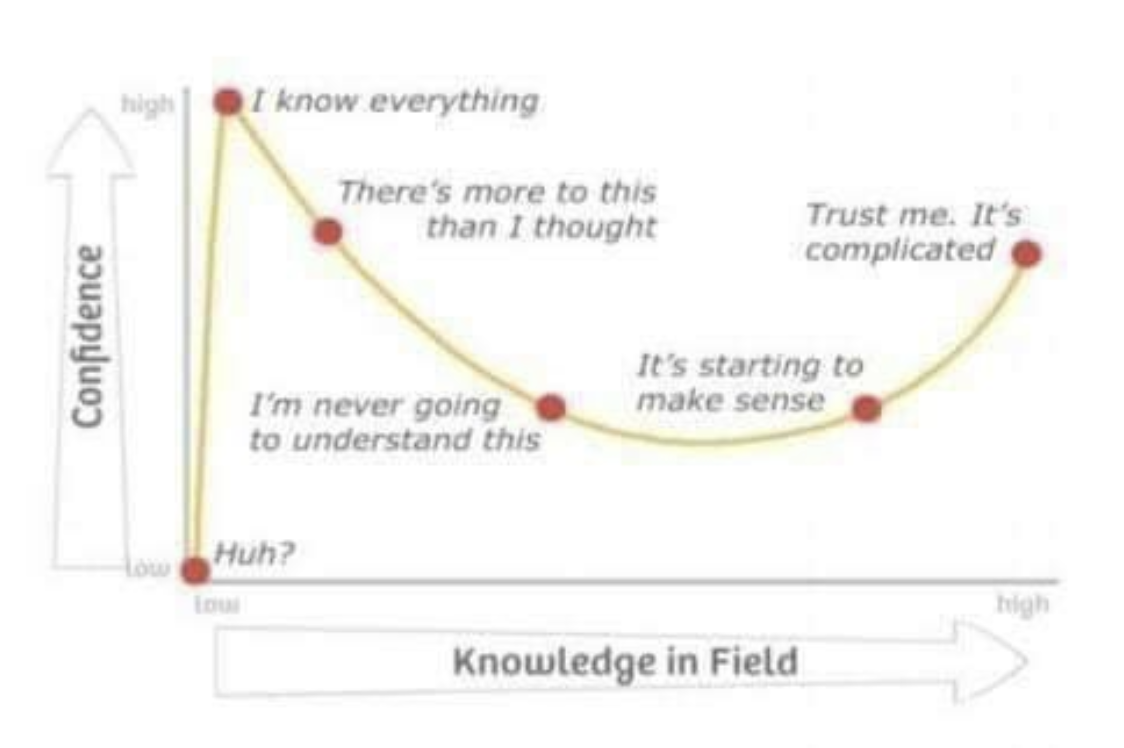

Take care, too, that you do not mistake the cautiousness of experts as lack of understanding. As Bertrand Russell said:- "The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are so certain of themselves, yet wiser people so full of doubts." The Dunning-Kruger Effect may be summarised as follows: The more you know, the less confident you're likely to be. Because experts know just how much they don't know, they tend to underestimate their ability; but it's easy to be over-confident when you have only a simple idea of how things are. This diagram summarises the effect rather nicely:

Non-Experts May Be Over-Confident

Boardrooms, universities, the media and many other places are full of people who have enormous self-confidence - and often a wide and influential network of supporters. That doesn't mean that they know what they are talking about, especially if pontificating about technical subjects, economics and management. Stick to your guns if you know better - though take care to consider how best to speak truth to power, if that is necessary.

Newly appointed Vice-President Lyndon Johnson was awed by his first encounter with the assembled brains of the Kennedy Round Table, only to be brought down to earth by Sam Rayburn’s comment that he would feel a lot better if just one of them had run for Sheriff once – or knew some Vietnamese.

Consulting the Public

It is in practice not easy to consult the general public, and the effort required can seem disproportionate to the benefit - but it is never disproportionate if it concerns their safety or welfare.

Probably the most important thing is that you should not be scared of people. The aftermath of the Grenfell Tower tragedy showed that you should trust people, listen to their leadership, and then either help them or get out of their way.

The lives and accountabilities of policy-makers and decision-makers are often very different to those of the people that will be affected by their decisions. Boundaries need to be crossed. and this can take courage on both sides.

You can start by ensuring that the consultation documents are written from their perspective and are available in multiple languages. Then give them enough time - 13 weeks minimum - to learn about and assimilate the content of your consultation document before using a response format that makes it easy for them to contribute. It can often be effective to use trusted intermediaries who might organise ‘citizens assemblies’ or who might train and pay local residents to run local consultation sessions and summarise responses to feed into the process.

Above all, talk to those who may be unhappy with your policies. They often have a good reason, which you need to bear in mind whether or not you can change the policy, or its detail, as a result. And don’t hesitate to let your decision maker have a short note of what you have learned. It might just make him or her think twice.

Be careful to frame your consultation questions in a neutral way - see the nice example at the bottom of this web page.

But you should also - when consulting communities - make it clear from the outset that they have a voice - an important voice - but not a veto. It is seldom, if ever, helpful to ask questions such as 'do you agree or disagree' which imply that your favourite option will not happen merely because sufficient numbers object. Arguments do not become any stronger as a result of being repeated by lots of respondents. Equally, one serious problem unearthed through consultation can be more than enough to kill a proposal, however many other respondents think it is a great idea.

Policy Reviews

It can sometimes make sense to appoint an expert individual or organisation to carry out a review of the available evidence and options, and to make recommendations. They can be supported by other experts or by your own staff. The key thing is to ensure that they follow the advice on this web page so that their recommendations are well-founded. Don't be tempted to appoint 'a big name' to carry out a celebrity review which will attract favourable media coverage but will also attract serious expert criticism, such as this from Jill Rutter. (Her full advice - 'Bad reviews' - is here.)

"The report ... does nothing to persuade people who might be sceptical of its proposal. There is no evidence, or modelling, of potential effects. Its process was closed. The commissioning process was unclear. There was a single reviewer representing only one side of the argument ... it lacked an effective champion within government – indeed the Business Secretary has gone out of his way to dismiss it. ... So far, [its] main effect ... has been to entrench pre-existing views.

The 'Valley of Death' between Policy and Delivery

Jon Thompson, the much respected Head of HM Revenue and Customs, used the above dramatic phrase, and made some telling points when addressing the IfG in 2018. He began by stressing that translating policy into delivery is one of the most complex challenges in government, and one thrown into sharp relief by austerity and Brexit. And he noted that a solid understanding of delivery also empowers civil service leaders to ‘speak truth to power’, and to advise Ministers on the timescales, costs and technical aspects of delivering their policies.

It is therefore absolutely vital to consult 'delivery partners' - those who will be responsible for delivering your new policies. They will have strong views about practicality, resources and communication. Ignore them at your peril. As Charles Dillow says, implementation is policy:-

Policy-making is not like writing newspaper columns. It's all about the hard yards and grunt work of grinding through the detail. A failure of implementation is therefore often a sign that the detail hasn’t been thought through, which means the policy itself is badly conceived. Reality is complex, messy and hard to control or change. Failing to see this is not simply a matter of not grasping detail; it is to fundamentally misunderstand the world. If you are surprised that pigs don’t fly, it’s because you had mistaken ideas about the nature of pigs. Bad implementation is at least sometimes a big clue that the policy was itself bad.

It is equally vital, of course, that you and senior managers in your deliver partners consult 'the front line' - whether it be members of the public, or your employees, or nurses or police officers etc. etc. The need for this was surely brought home to everyone by the tragedy of Grenfell Tower. Gill Kernick commented as follows:

“For the last 10 years I have worked predominantly in high hazard industries looking at how you create safe cultures … and specifically how to prevent major accidents – low probability, high consequence events. The key to change is creating a connection between the most senior levels of the organisation and the front line. … In the case of housing, because of the complexity of the world we live in, it is the tacit knowledge of residents that is critical to keeping people safe. They have the experience of living in the building, they know what the issues are, and they probably know how to solve them.”

Pilots and test areas can be very useful, although politicians may be concerned that they send a signal that they aren't sure that the innovation is a good idea.

Finally, remember that there is a crucial difference between releasing information and informing the public. The wholesale release of vast amounts of data does not of itself inform anyone. There should of course be no question of hiding or distorting information, but care should be taken to ensure that the overall effect of the release of information is to improve recipients’ understanding of the issues (and the uncertainties) rather than simply to add to the confusion. Frank Zappa summarised this very well when he said that 'Information is not knowledge'.

[Government officials are generally pretty keen to publish research and other evidence and many departments do publish huge amounts of material. But officials will be aware that their principal function is to support the government of the day, and they may therefore on occasion ask themselves whether publication will cast too much doubt on settled government policy.]

Advice for Officials

Please follow this link to access more detailed consultation advice for public sector policy makers. Civil servants should note in particular the requirement to prepare impact assessments for new regulatory and deregulatory measures, and to submit those with an impact of more that £5m pa to the Regulatory Policy Committee.

And it is worth bearing in mind that many commentators, including myself, used to argue that successive British governments had over many decades slowly abandoned telling the public how to behave and what to do ('Westminster knows best') and and instead had become much better at genuine consultation, recognising that modern citizens need to be led, with their consent, rather than orders around. But Jeremy Richardson published a rather depressing blog in 2018 in which he argued that that trend had been reversed. A consensual, collaborative and deliberative policy style had been replaced by a much more impositional style. But plenty of scope for good practice remains and is summarised above. Please do your best to follow it, even in the face of political opposition.