This Section contains various tongue-in-cheek advice about working in the UK Civil Service. But don't forget that many a true word is said in jest ...

First, I have brought together some excellent advice from Wilfred Hyde and Giles Wilkes In Policy-Making 101.

Now let's learn how to interpret the civil servants' favourite language ...

Mandarin.

It is of course no accident that Whitehall officials are known as Mandarins. Their language is often as hard to understand as anything spoken in Beijing. These first 9 lessons, mainly written by David Fuhr and Martin Jones, with a contributions from Jo Rixom, will provide you with the basic language that you need to get by and survive in Whitehall.

Lessons 1 & 2: Basic Vocabulary: What your Bosses Really Mean - and ...

the Whitehall Clock and Calendar

Lesson 3: Basic Vocabulary: Policy Development

Lessons 4 & 5: Communicating with Ministers' Offices - and ...

Management Speak

Lessons 6 & 7: How to Write Government Documents - The Title & The Foreword

Lesson 8: How to Write Government Documents - The Text

Lesson 9: Understanding Drafting Meetings

Masterclasses

Lesson 10 is a Masterclass by Lord Butler.

Lesson 11 provides sage advice from Sir Humphrey Appleby on how to survive Ministers' attempts at Civil Service Reform.

Snakes and Rats

The Armed Services are not great fans of the civil service. I was therefore pleased to find that the various elements of the military also like to joke about their own colleagues Here is How the Military deal with Snakes.

Not to be outdone, a senior official recounts How the Senior Civil Service deal with Rats.

Communicating with (other) Europeans

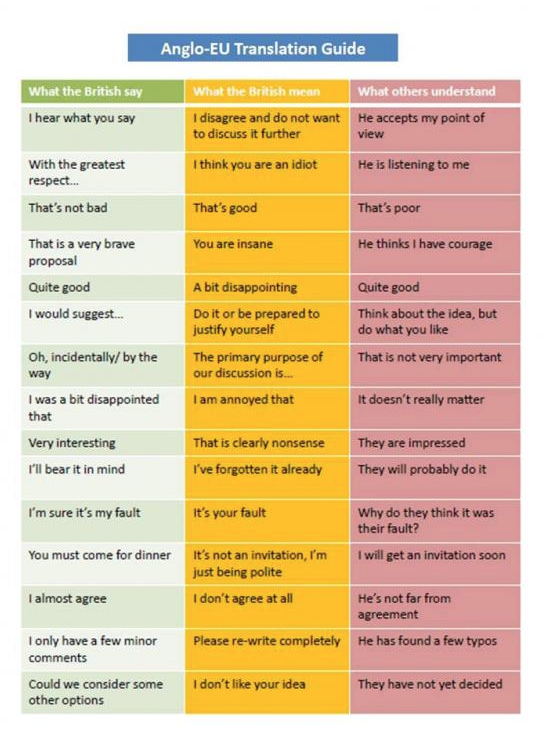

The English seldom say what they are really thinking, and this trait is amplified to a truly dangerous extent when we communicate with those on the other side of the Channel. Watch out in particular for these mistranslations:

Communicating with Americans

The differences between American and 'English' English are usually very clear but some subtleties can cause problems. Here is one example:-

A question such as "Would it be possible to ...?" would be heard by many Americans as quite genuine, and a negative response would be perfectly polite. To the English, though, such a question gets pretty close to being a command.

Similarly, I well remember an American parent asking a British school Principal whether the parent could remove their child from school for a short holiday. "I would rather that you didn't'" was taken as reluctant permission ... which was absolutely not the Principal's intention.

And Finally ...

The correct collective noun for civil servants is a Meeting.