General advice for policy staff engaged in consultation - whether in the public or private sectors - may be found here.

This web page contains more detailed consultation advice for local authority, central government and other public officials.

The latest version of HMG's consultation principles is here.

Consultations Leading to Decisions

Regulators and other officials who are implementing specific laws need to consult those likely to be affected by their decisions - and indeed others who may have advice and information which might help them reach fair and sensible decisions. The terminology varies from institution to institution but -

- The formal process begins with the publication of an Issues Statement defining the decision that is to be made, and listing the main matters to be taken into account in reaching that decision

- At around the same time, there is a call for relevant advice and information

- Once a likely decision emerges, there is a 'minded to' document - which regulators often call Provisional Findings. It explains in some detail why the decision-maker is minded to make the decision in prospect. It should if necessary include an impact assessment - see further below.

- A final decision document, again with detail, is then published a little later, usually confirming the provisional decision, but sometimes not, if important new information or argument has come to light.

Impact Assessments

The preparation of these documents should not be seen as a chore, but rather as an important activity which ensures that any regulatory or deregulatory recommendations are sound. If you are thinking sensibly and thoroughly as you develop policy, the impact assessments should almost write themselves.

The first impact assessment should include a clear statement of the policy objectives as well as an initial assessment of the risks, costs and benefits of regulation, as well as why non-regulatory options – including doing nothing – are unattractive. Later assessments will build on these foundations, adding more detail and more certainty, and should be be published as part of the formal consultation process and alongside draft legislation. All central government regulatory and deregulatory measures should have an impact assessment, and those with an impact of more than £5m pa should have the IA scrutinised by the Regulatory Policy Committee.

It cannot be stressed too strongly that IAs are very important documents, whose preparation needs to be properly planned and resourced, and started early enough to form a genuine part of the decision making process.

Behaviour will not change as much as you think

You must be careful not to be too optimistic about the scale of the benefit from your intervention. Here are some examples:

- Many people will leave energy-efficient light bulbs on for longer than they would if the bulbs were consuming much more power. (I confess that I do!)

- Researchers have shown that statins and blood pressure medicines are probably less effective because those that start using them are then more likely to allow healthy habits - such as taking exercise and eating carefully - to slip.

- Most of us have what might be described as a risk appetite so - if an activity is made safer than before - we will behave less carefully. More detail is here and a broader discussion of the regulation of health and safety can be accessed here.

Unintended Consequences

It is also important, whether you are imposing taxes, spending money, or drafting domestic legislation, that you take care to avoid or mitigate unintended and unwanted consequences, and (if regulations are necessary) to regulate in such a way as to encourage compliance and deter evasion. Let’s look first at unwanted consequences. Compliance is discussed separately.

The window tax is probably the best known example of a tax that was easily avoided by bricking up windows, or designing new buildings with fewer windows. But it is usually forgotten that the principal undesirable and unintended consequence was that the tax led to reduced light and ventilation, especially in city tenements where workers congregated as the industrial revolution got under way. This revenue-raising measure therefore exacerbated the spread of disease and hastened many deaths.

H L Mencken once said that "There is always a well-known solution to every human problem - neat, plausible and wrong". The problem is that it is, by definition, very difficult to identify unintended consequences – and this is one of the main reasons why genuinely open-minded consultation is so important. It might help if I list the sort of unwanted consequence that can occur:

- A risk-free food chain might raise costs (to the detriment of the poor), restrict imports (to the detriment of the third world) or sacrifice taste and texture for the monotonous security of the can.

- Attempts to reduce sports injuries might well generate poor health as a result of reduced physical activity.

- Expensive railway safety might increase fares and so divert traffic to more dangerous urban roads.

- Research has shown that exposure to 'fake babies' (that cry, urinate and require to be fed around the clock) leads to higher rates of teenage pregnancy.

- Attempts to create risk-free child-care might reduce the availability of such care.

- The risk to a child living with inadequate parents needs to be balanced against the risk of the damage that would arise from enforced separation.

- UK-only regulation might, if it were to increase the price of UK goods, lead to increased sales of cheaper unregulated goods from abroad.

- A cull of ferrets on Rathlin Island ended up doubling the population because the remaining ones had more resources which encouraged additional breeding.

And civil servant turned academic John Hilton noted the following, after the introduction of employment benefit :

When I [previously] visited the North East , a crowd of young men ... beset me each time I came into Newcastle station, wanting to carry my bag. I went to Newcastle on this present tour but no-one wanted to carry my bag. There are 6,000 unemployed men in Newcastle but none wants to earn a shilling by carrying a bag [for fear of losing unemployment benefit]. To be seen earning a shilling is a terrifying prospect. The regulations may provide for such things but the unemployed man does not know what the regulations are and the last thing he wants is to stir up mud ... Beyond this is the barrier set up against a man working an allotment, keeping chickens ... How far can he go while keeping his title to benefit? No-one knows; better not to take risks.

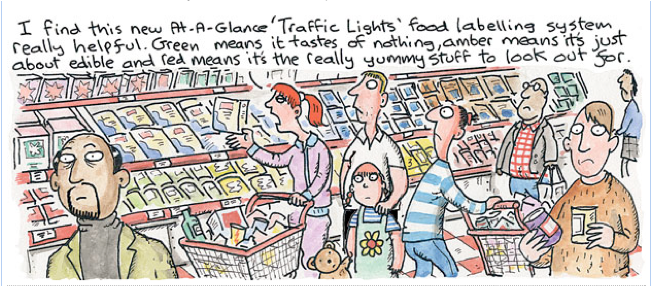

Here is rather more tongue-in-cheek example:

Publishing Taxpayer-Funded Research

The 2016 Sense about Science Missing Evidence report expressed concern that taxpayer-funded research is not always published in sufficient time for informed public discussion. The reasons, in addition to political concerns about the timing of publication, may include uncertainty about peer review, about what counts as government research, and about what should be published in relation to policy announcements. "Yet delayed publication can be as damaging as indefinite suppression because it deprives parliamentarians, the media, NGOs and others of the timely access they need in order to be able to engage with policy formation in the light of contemporaneous evidence." Drawing up and announcing policy decisions before the media and public are able to scrutinise the expert advice that ministers have based it on can result in debate being "handicapped or stifled".

The report's author, Stephen Sedley, acknowledges that there will "always be cases in which government is doubtful about or dissatisfied with the quality" of research it has commissioned, but he argues that this should not justify withholding its publication, pointing out that departments should feel able to set out their grounds of doubt or disagreement with such advice when they do make it public. And delaying the publication of such research "simply to avoid political embarrassment" is not "ethically acceptable".

The Law

You should consult because it is sensible to do so. But a number of court cases have stressed that public servants have a legal duty to consult. You should consult your legal adviser if and when necessary but, briefly, judges have ruled that:

The three main purposes of consultation are

- (i) to improve the quality of decision making,

- (ii) those affected may have a right to be consulted by it and feel injustice if they do not and

- (iii) consultation is part of a wider democratic process

And a duty to consult may arise:

- (i) where there is a statutory duty;

- (ii) where a promise to consult has been made;

- (iii) where there is an established practice of consultation and

- (iv) where it would be conspicuously unfair not to.