Guy Fleetwood Wilson was born in Florence, Italy in 1850.

He was a fascinating and remarkable man, and a great risk taker, including big game hunting on foot in India when in his 60s. This led to his coming face to face with wounded tigers and infuriated buffaloes, one of which charged him and inflicted serious injuries. But he was very cautious with money. Indeed, such was his reputation for holding the purse strings tight that disappointed applicants from Whitehall referred to him as “Not-a-Bob Wilson. But a grateful government was more impressed - he was created K.C.B. (1905) and K.C.M.G. (1908) when he became Finance Member of the Indian Viceroy's Council.

Guy Fleetwood Wilson was born in Florence, Italy in 1850.

He was a fascinating and remarkable man, and a great risk taker, including big game hunting on foot in India when in his 60s. This led to his coming face to face with wounded tigers and infuriated buffaloes, one of which charged him and inflicted serious injuries. But he was very cautious with money. Indeed, such was his reputation for holding the purse strings tight that disappointed applicants from Whitehall referred to him as “Not-a-Bob Wilson. But a grateful government was more impressed - he was created K.C.B. (1905) and K.C.M.G. (1908) when he became Finance Member of the Indian Viceroy's Council.

His early civil service career was not initially out of the ordinary until he became a Private Secretary and thus drawn to the attention of Ministers and senior officials who appreciated both his efficiency and enterprise. Probably the best example of the latter occurred during unrest, in 1890, amongst the Metropolitan Police which had culminated in the dismissal of 39 young constables. This allowed a riot to develop in Bow Street, where the constables had been based, led by ruffians who professed support for the sacked constables who in turn appeared to support the rioters. Guy Fleetwood Wilson described his involvement as follows:

One evening in July, 1890, I was sent for in hot haste to meet my Secretary of State [Edward Stanhope] at the Horse Guards, of all places. On arrival I was taken in charge by a colossal Lifeguardsman and conducted to the officer's room. They dined at St James's, so it could hardly be called a mess-room. In it I found seated disconsolately at a table and almost in the dark Mr Stanhope and the Home Secretary. The Chief Commissioner of Police walked out as I walked in.

They looked, and I am quite sure they were, frightened out of their wits. They informed me that the Bow Street Division of the Metropolitan Police had mutinied, that great trouble was anticipated, and instructed me to "find someone and tell him to send a battalion of Guards at once to Bow Street." I looked from one to the other and nearly burst out laughing. I could not conceive that they were in earnest. But they were, and in deadly earnest, so off I went.

I happened to know that Colonel Maitland Crighton was Field Officer in Brigade Waiting, and I knew also that he was not very well, so I counted on finding him at home. I duly found him, told him what had happened, and asked him to move a battalion to Bow Street. He flatly and quite rightly declined to do anything f the kind without a written order. I stepped up to his writing-table and wrote on a sheet of notepaper: "I am authorized by the Secretary of State for War to request you at once to send a battalion of foot-guards to Bow Street to maintain order there," and I appended my signature. To my great surprise he wads quite satisfied, and in an incredibly short time the Chelsea battalion was on its way to Bow Street at the double. When it got there things had quietened down and the Guards went home to roost.

Next day [General] Wolseley not only approved my action but expressed his approval officially, so all was well which ended well, but I have often wondered what would have happened to me if it had ended badly. No doubt I was to blame in acting thus "on my own," but I think it will be conceded that equal blame attached tom the Cabinet Ministers who deliberately allowed the full responsibility to rest on a young official occupying the subordinate position of private secretary.

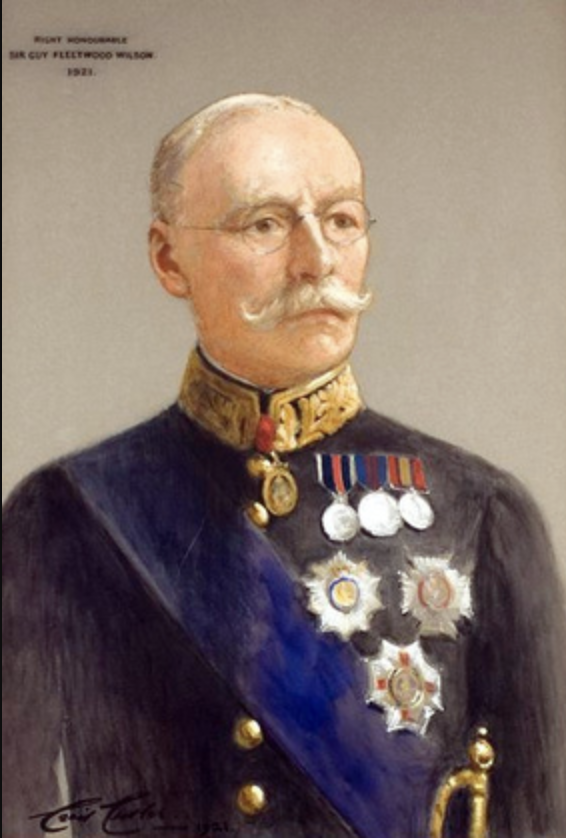

Sir Guy, as he had by then become, published his very readable memoirs in the form of Letters to Somebody in 1922.

A Little More Detail

Sir Guy joined the Civil Service in 1870, and retired from the Home Service in 1908 as DG of Army Finance. He then went out of India as Financial Member of the Viceroy's Council. He became acting Viceroy in 1912-13 after Lord Hardinge was almost assassinated, whereupon Sir Guy was called upon to deliver the Viceregal speech himself from manuscript stained with the blood of its author. He 'retired' after 43 years service in 1913, and gave another 13 years as member/chairman of various commissions, etc. He died in 1940 at the age of 90.

When he took the finance position in India he inherited a huge deficit which he eliminated mainly through various reforms and efficiency drives rather than increasing taxation. But this austerity, as we would call it, led to what his obituarist called 'one serious blot on his stewardship' as he left the Indian Army poorly equipped (having 'disregarded the appeals of Army Headquarters') and in particular poorly equipped for the Mesopotamian campaign at the beginning of the First World War. Although initially successful against Ottoman forces, a British led Indian force was eventually besieged for four months in Kut, and forced to surrender.

I am greatly indebted to Zeb Micic for drawing my attention to Sir Guy and his memoirs.