I guess that most people are born able to prepare a good speech, just as they can learn any language. Unfortunately, the ability is usually knocked out of us as we become self-conscious. Our working lives are also dominated by the written word. The following tips are intended to help those who wish to re-learn the ability to write an interesting speech, whether for a Minister, a colleague or themselves.

To begin with, you must first be absolutely clear whether the speech needs to be delivered in the first place. Speeches are very time-consuming, both in their preparation and in the travel time to and from the venue. When ministers give speeches they need to tread a fine line between being dull and dangerous. Are you sure that the Minister will have something interesting and/or original to say, and will not be unnecessarily political or controversial? If so, is the audience the right one? Will there be an opportunity for publicity?

If in doubt, remember how embarrassing it was when Prime Minister Tony Blair was slow hand-clapped by the Womens Institute. Commenting many years later, Polly Toynbee noted that:

"Week in, week out, flotillas of Ministers stand up in front of audiences of all sorts and read out speeches badly written by someone else, platitudinous and patronising. ... All organisations are thrilled to get a headline Minster to speak as a crowd puller ... In the audience will be workers, professionals and experts [who] will know a hundred times more about the subject than he does. [After a very predictable and boring speech, the first or second questioner] begins to explain how life is out there. ... Suddenly the meeting springs into life. The Minister starts for the first time to speak like a normal human being ... there is a dialogue. The Minister listens. ... when out of the shadows steps the ministerial minder, pointing to his watch. Before you know it, the great man has gone. What does he leave behind? A very angry room. ... The Minister's visit has had precisely the opposite effect of that intended. Cynicism about politics is redoubled."

Even worse, all too many invitations are from organisations that need to fill an after dinner slot or something of the sort. The last thing they want is a thoughtful speech about the weighty issue of the day – especially if the content might be critical of the community to which the audience belongs. Let’s face it: half the audience will be tipsy – or worse – and the majority will certainly want to be entertained. Leave these challenges to professional after dinner speakers. I have only once agreed to speak at evening functions, and performed so abysmally that I swore never to do so again. If a Minister wants to appear for political reasons, or to raise his or her profile, then let the Special Adviser write the speech. They will know more jokes than you do.

But a properly prepared speech, delivered at the right time to the right audience, can of course be highly effective. As ever, planning and preparation are the key.

First, remember your three duties and decide which you are carrying out when drafting the speech. Is the Minister going to talk fairly freely about possible policy developments? Or are you helping to promote or defend Ministers’ policies? - in which case a more barn-storming approach will be needed. Or maybe you are even in implementation mode, which would require a quite different approach again. But do bear in mind that many audiences object to simply hearing the party line. A more considered, thoughtful and consultative speech will generally go down much better.

Second, you also need to identify those one or two key messages that you and/or the speaker want to leave in the minds of the audience. What do you want them to do differently after hearing the speech? What do you want them to remember some days afterwards?

Third, you should also find out what the audience wants to get out of the speech. The easiest way to do this is to ask the event organiser what will go down well, what information needs to be put over and what will please the audience. Your one – or at the most two – key messages can then be nicely wrapped so that the audience is first made receptive to the key messages – especially if they are likely to be unwelcome or surprising.

Take particular care correctly to define and describe the nature of the speech. A ‘keynote address’ should include the key points which will be the main topics for discussion for the rest of the conference. An ‘opening address’ will set the scene or set out the Government’s position as a prelude to more detailed speeches. In this case you should take care that the Minister’s comments will not duplicate any other opening remarks by the Chair or host.

And don't get too carried away! Daniel Finkelstein admitted that "When I wrote speeches for William Hague he used to congratulate me on the text. He said I had drafted for him an oration perfect for delivery from the steps of the Lincoln memorial as the million men arrived from the Capitol. Then he would remind me that he was in fact addressing the Christmas Club supper of the Durham Conservative Association."

When you have decided what you want to say, then plan your structure. You can do much worse than stick to the traditional:

- Tell them what your main message will be, then,

- Deliver the message, and then,

- Tell them what the message was!

There may be other ways of structuring a speech, but no other way works every time, or leaves such a clear impression.

Drafting: The worst thing you can do is either ‘draft’ or ‘write’ a speech. If a speech reads well, especially to colleagues, it will sound stilted and boring. We naturally speak in 2-3 second bursts. We write using longer sentences.

You should simply pick up a pen or sit at your keyboard, put your speech structure on the table in front of you, and start writing or typing. If you get stuck, think about the audience and talk about them and the issues that face them. Use plenty of anecdotes and illustrations, avoid long lists, and ditch detailed statistics in favour of easily grasped facts (e.g. ‘last year we doubled our exports to X’ rather than ‘in 2022 our exports to X were 92 per cent up on 2021’) . Above all, get some emotion into it, and some power. The result will be much more interesting – and more natural.

Then check the typed text for unclear or misleading phrases; remove platitudes and generalities; and check that it consists only of sentences which are less than two lines long. Finally, read the whole thing through out loud, to make sure that it trips off the tongue fairly easily. Do not, as has happened, ask a Minister to describe how he has ‘instituted an epidemiological survey’.

You will of course need to show the draft to colleagues affected by its content. But, unless it contains a major statement of Government policy, try to avoid showing it to senior colleagues. They will only start fretting about the colloquial language and the split infinitives, and turn the whole thing into an essay which will read well, but sound awful.

On the day, always check the technology. Is the speaker familiar with the microphone and teleprompter, and do they work? Ditto the projector and video player. Does he or she know how to control them?

It is also worth listening carefully to the speech, even if you know every word off by heart. Try to tune into the Minister’s speech patterns, sense of timing etc. You will never mimic them exactly, but it will help you when you next settle down to dictate a speech.

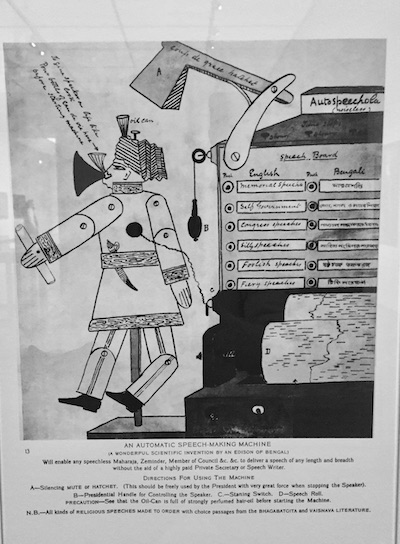

And afterwards check how the speech was received. Congratulate yourself (and the speaker!) if it went well. If it went down badly, you can always quietly blame the speaker and console yourself that this happens to everyone. Either way, you will learn something for the future .... 'though you might wish that someone had indeed invented an automatic speech-making machine ...

Presentations

I recommend Tessa Davis' advice on making less formal presentations.