This note summarises developments after the June 2017 General Election. Other notes in this series are listed here.

'The Dead Generalist'

In July 2017, Ed Straw drew attention to his above provocatively titled pamphlet, first published in 2004, arguing that civil service reform was still needed for two reasons:

-

'As the old politics of redistribution and mediating between classes have diminished in relative importance, the new politics of competence in public service delivery and in national decision-making have come to dominate: the civil service is central to the capacity of any government to deliver public services. This is a new challenge with which politicians and civil servants are wrestling. The front line is deeply affected by the centre.

- Despite all of the proposals, the fundamentals of the system have not changed. Indeed, the fundamentals can be defended vigorously, and it is these fundamentals which most need to change. The civil service system has not experienced the sea change which most of the rest of the country, in the public and private domains, has undergone. Our public debate has assumed for decades, if not generations, that the principles of civil service organisation are somehow sacrosanct, and that methods first outlined 150 years ago remain the best way to organise public administration today. "

The report then turns to what the author describes as 'the independence imperative**' of the civil service which 'creates an organisational paradox. Ministers are accountable to the electorate for delivery, and yet themselves appoint almost no one to oversee it. Imagine becoming chief executive of a large organisation and being told that the entire management are ‘independent’, that you have no control over their major levers of motivation – recruitment, promotion and reward – and that they operate as a separate organisation with a mind of its own. Modern organisations do not and cannot work like that. Neither can government.'

Powerful and effective initiatives can still be successful, it is argued, but only rarely and by forgoing 'the traditional civil service approach', as exemplified by the rough sleeping initiative which was led by a specialist from outside the civil service with strong sponsorship from the Home Secretary. Here is a comparison of the two approaches as described by the formal evaluation of the initiative:

Traditional Civil Service Approach v. Rough Sleeping Approach

- A generalist is assigned to it v. Led by a deep specialist/ practitioner

- Staff assigned to the job, from the civil service v. Staff hand-picked for the job from a range of backgrounds (including the civil service)

- Largely office-bound v. ‘Service sampling’ approach: i.e. management and staff out experiencing the services with the users

- ‘Passing-through’-orientated v. Goal-orientated and time-limited

- Issue guidance and wait for the world to change v. Committed, well-led, motivated group

- Future careers dependent on serving inside v. Future careers dependent on success with this objective

- Analyse the problem academically and as a policy matter v. Analyse the problem from the ground and from the customer, and redesign the services accordingly

- Impartial v. Passionate

- Dominated by departmental silos v. Joining up services

- Basic assumption is to carry on as before v. Explicit about the need for change

- Change has to be justified v. Challenge assumptions and working practices, and do things differently

The second part of the report proposed the shape of a new civil service which was intended to:

- 'End the separate existence of the civil service and its isolation; to make it part of the government of the day; and to start joining it up with the public services it exists for.

- Give governments and ministers the authority and resources they need to deliver on election commitments.

- Create clarity of role, and separate the independence-driven roles from the roles of service delivery and of parliamentary, political and legislative management.

- Adopt and apply organisational best practice with particular impact on the sourcing and motivation of people.

- Undertake change at quick pace.

- Put in place a new framework to drive understanding and improvement, independent of ministers and civil servants; to keep national scores; to evaluate departments, delivery and initiatives; and most importantly, to become the hub of a powerful force for international knowledge acquisition, diffusion and learning.'

**Pedantic note:- I don't think that 'the independence imperative' is quite the right phrase. Unless you are a government minister, the civil service looks far from independent from its political masters, not least because of the strictures of the Armstrong Memorandum. But the analysis of the paradox later in that paragraph has real force.

Comment

It is surely hard to disagree with the broad analysis summarised above, nor with much of the detailed prescription for change which completes part two of the report. It is hard to disagree, too, with the report's prediction that its recommendations would meet much resistance, including from the civil service itself which 'is often insular and internally focused' as well as from the 'opposition of the day [which] has always seen most advantage in defending the civil service from government ‘politicisation’ rather than in backing reform to its own long-term advantage. The short-termism of our modern democracy stymies reform.'

Mr Straw correctly noted that 'none of the civil service reforms [since Northcote Trevelyan] have ever addressed change in [his] comprehensive and aligned way' and concluded that 'Tackling the issue will take skill and courage.' I am less convinced by his assertion that reform 'is a day one issue, in that the longer a new government is in office the more it gets stuck with the status quo and cannot break free. Day one is the first day after the election of a new prime minister or of a new party in power.' My own view is that progress can only be made on a cross-party basis - not least because of the short-term politics identified by the author.

A more detailed analysis of the repeated failure of attempts to reform the civil service may be found in my webpage discussing Civil Service Reform Syndrome.

Professionalising Whitehall

The IfG published the above-titled report in September 2017, commenting as follows:

If the UK Government is to succeed in negotiating the complex challenges that it now faces, the civil service must have the specialist capability that it needs. Over the past four years, the leadership of the civil service has stepped up efforts to professionalise key activities such as policymaking, financial management and commercial procurement and contract management. Professionalising Whitehall takes stock of the reform efforts under way in eight core cross-departmental specialisms ... and ... offers an assessment of where these specialisms are at now, and argues for four priorities for reform.

One recommendation was that civil service leaders must tackle the “entrenched perception” that Whitehall policy roles are the best way to reach senior posts. In particular, the leaders of each profession needed to ensure that civil servants gained greater access to training and mentoring on how to operate within a political environment and influence policy. This would help specialists progress to senior management positions within departments and make a career in specialisms outside policy more attractive.

Meanwhile in Whitehall ...

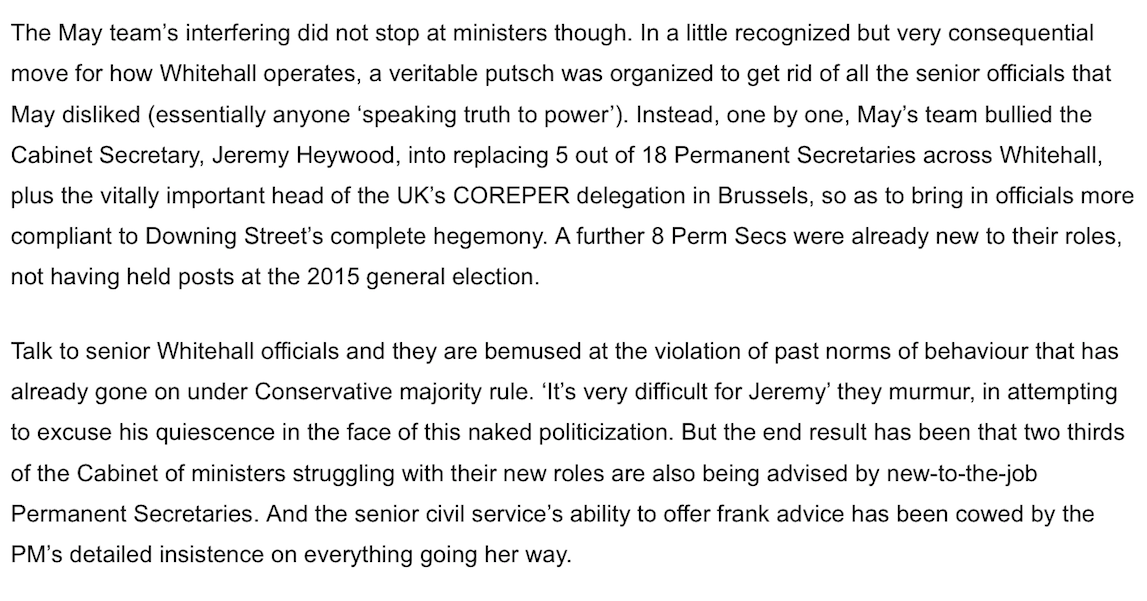

... reports suggested that Prime Minister May was not getting the best out of her increasingly cowed senor officials:

There was a particular problem in that she had appointed one of her favourites, Ollie Robbins, simultaneously to report to her and, as his Permanent Secretary, to Brexit secretary David Davis. The latter inevitably fell out so Mr Robbins was moved into No.10 Downing Street in September 2017.

Universal Credit

This much delayed and much criticised program ran into further flak in late 2017 with the House of Commons Library reporting that "Emerging evidence points to a number of problems for claimants in Full Service areas, including:

- financial hardship and distress caused by lengthy waits before the first payment of UC is received, compounded by the 7-day “waiting period” for which no benefit is paid;

- some, particularly vulnerable claimants, struggling to adapt to single, monthly payments in arrears;

- inflexible rules governing Alternative Payment Arrangements such as direct payment of rent to landlords;

- increases in rent arrears, with serious consequences not only for claimants but also for local authorities and housing providers, as a result of exposure to greater financial risk;

- homeless claimants unable to get help with the full costs of emergency temporary accommodation.

- issues with registering and processing claims – e.g. online claims being rejected or “disappearing”, awards not including the housing element due to problems verifying rent payments;

- a lack of support from jobcentres for claimants without ready access

to a computer or with limited digital skills/capabilities; - lengthy, repeated and expensive calls to the UC helpline to resolve problems;

- increasing demands on support and advice services from local authorities, housing associations and charities as a result of having

to assist UC claimants; - insufficient funding from the DWP for local authorities and partner organisations providing “Universal Support”, such as budgeting advice;

- third parties facing difficulties resolving claimants’ problems due to the DWP’s insistence that the claimant must give explicit consent for an adviser to act on their behalf."

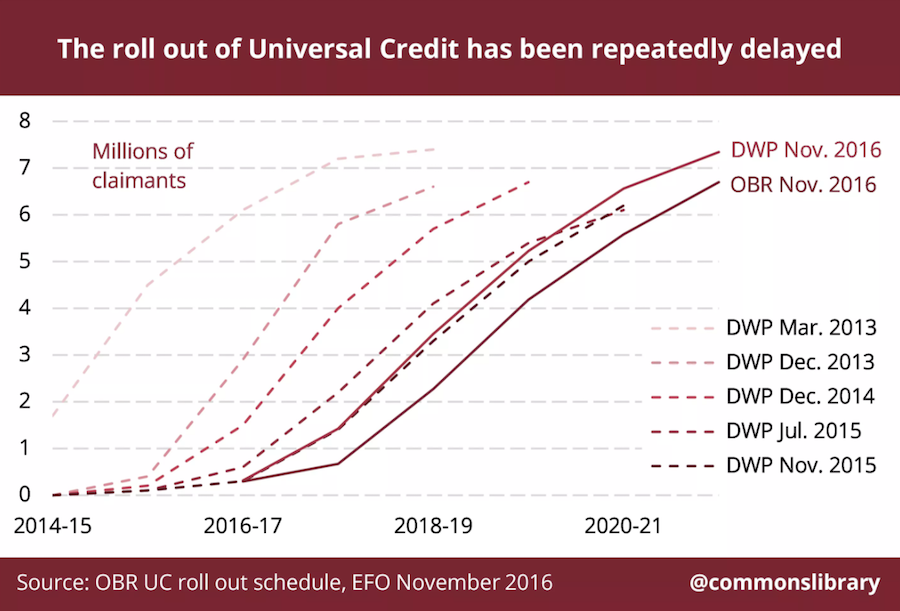

The Library also published this chart, which speaks for itself:

Some argued that Universal Credit (and possibly also Brexit) were good policies, badly implemented. But Chris Dillow disagreed and argued that implementation is policy.

"A failure of implementation is ... often a sign that the detail hasn’t been thought through, which means the policy itself is badly conceived. Reality is complex, messy and hard to control or change. Failing to see this is not simply a matter of not grasping detail; it is to fundamentally misunderstand the world. If you are surprised that pigs don’t fly, it’s because you had mistaken ideas about the nature of pigs. ... Bad implementation is at least sometimes a big clue that the policy was itself bad."

Either way, one is forced wonder whether the civil service good have done more to help or persuade Ministers to improve the design of the policy and/or its implementation. It is though fair to point out that Ministers' principal objective for the Universal Credit appears to have been 'to make work pay', rather forgetting the rather more fundamental objective of providing social security for the unemployed and those who cannot work. This suggests that Chris Dillow's thesis holds true and that it was the conflicting policy objectives that eventually created the largest implementation obstacles.

NAO's Views

Amyas Morse, Head of the National Audit Office, made some interesting comments when he appeared before the re-commenced PACAC inquiry into Civil Service Capability. He repeated his by now well-known views that many officials feared that offering ministers constructive criticism would damage their careers. It would be helpful, he said, to find ways to make ministerial directions more common and acceptable. Circumstances where officials seek written direction from a secretary of state to pass up the responsibility for a particular use of public money were currently quite “rare” and “often on a technicality. A Civil Service World summary of his evidence is here

John Major's Speech

John Major made an interesting speech The Responsibilities of Democracy late in 2017 in which expressed concern about the way in which the civil service had been "undermined by its own masters". "It is in our national interest that public service should remain a career that attracts some of the very best brains in our country. We should value it, not disparage it."

"Why Whitehall is Struggling with Brexit"

Former Chancellor Lord (Nigel) Lawson attracted some attention in January 2018 when he told the BBC that civil servants would "do their best to frustrate [the Brexit] process because it goes against the grain so fundamentally ... Brexit is a most radical change of direction for this country. The idea that any bureaucrat could be in favour of radical change is a nonsense. Bureaucrats by their very nature loathe radical change of any kind."

But a closer examination of his comments revealed that he was making a perhaps more serious criticism of the current government:-

"... officials equally realise their constitutional duty to accept the leadership of the politicians, of the elected government. ... I was... a member of the Thatcher government. We came in and introduced radical change in economic policy. All the officials were aghast. They thought it would be a disaster. But at that time we had a strong cabinet led by an outstanding prime minister and they accepted the political leadership as is their constitutional duty. So we made this radical change and it worked out very well. It is really the job of the government, the cabinet and above all the prime minister to force this through."

James Blitz subsequently offered this sensible analysis in the Financial Times:- Why Whitehall is struggling with Brexit

Lord Lawson, the former Conservative chancellor of the exchequer, recently launched a broadside against the UK civil service over Brexit. ... Reading today's annual report on the state of Whitehall from the Institute for Government, one could be forgiven for taking a different view. Civil servants seem to be doing their best to implement an orderly Brexit. The trouble is that political decisions by ministers are making the process much harder.

Three points from the IFG report illustrate this. The first concerns the degree to which Theresa May has reshuffled her ministerial team since coming to power in July 2016. True, the top level cabinet posts have barely changed, as Mrs May tries to maintain a balance between Leavers and Remainers in her entourage. But according to the IFG, some 85 of the 122 ministers across government (71 per cent) are new in post since last year’s general election. Given that most departments are heavily affected by Brexit, this seems a remarkable — and unhelpful — amount of ministerial churn. It has been especially acute at the Department for Exiting the EU where, for example, the minister in charge of managing Brexit through the Lords has now changed three times. The risk is that change on this scale favours short-termism over depth of knowledge.

The second decision that may have made it harder to implement Brexit was the move back in the summer of 2016 to set up Dexeu in the first place. According to the IFG, the government has recruited some 8,000 additional staff across government since the referendum — and this is understandable, given how mammoth a project Brexit has become. But questions linger about the decision to set up Dexeu rather than co-ordinate Brexit policy through a European secretariat at Number 10 (as is now increasingly happening). The IFG report suggests that while morale at Dexeu is high, staff there do not look settled. Dexeu had two permanent secretaries in 2017 and staff turnover is 9 per cent a quarter — when that of most departments is 9 per cent a year. As one former civil servant recently told me: “It’s clear that the leadership of the [Brexit] process and strategy has gravitated into Number 10. So the bright staff will know where the action is, and will jockey to get in there, rather than being beached in Dexeu with little idea of what is going on.”

The third point regards the number of projects Whitehall is undertaking overall. Given that Brexit is such an immense task, one might have assumed that ministers would ease up on some of the other things the civil service is doing. But they are not. The Infrastructure and Projects Authority oversaw 143 government major projects in 2017. That is the same number as it did in 2016. John Manzoni, the chief executive of the civil service, said in 2016 that Whitehall is doing “30 per cent too much to do it well”. But ministers don’t appear to be listening. As a result, according to the IFG, the government is now confident of successfully delivering just one-in-five projects.

Brexit is the biggest challenge facing Whitehall since 1945. The impression from the IFG report is of a civil service that is struggling to cope under the pressure. The Brexit legislative programme is behind schedule; departments are being less and less open about what they do; major projects, even if unrelated to Brexit, are more and more at risk. Pace Lord Lawson, these problems have not been generated by civil servants. Much of the difficulty is down to decisions taken by politicians — often from Number 10 itself.

The Universal Credit Saga Continues

The House of Commons Works and Pensions Committee continued to be unimpressed with the planning and management of the roll-out of Universal Credit. In their January 2018 report they said that:

'In 2013 the UC programme was on the brink of complete failure. It is to the Department’s credit that it has brought it back from that brink. Though it has been subject to extensive delays, the programme is now run more professionally and efficiently with a collective sense of purpose. It continues, however, to face major challenges. Chief among these is automating the service. While the Independent Project Authority's (IPA’s) call for the “industrialisation” of UC for complex cases and vulnerable customers is an unfortunate choice of phrase, UC can only deliver its promised efficiency gains if it becomes cheaper and less labour-intensive. The Department has consistently struggled to convince the IPA that UC can scale as planned. The Department must balance the considerable costs of further delays against the costs of pressing ahead. The “firebreak” in the rollout in January 2018 and the full business case, which was due in September 2017 and is [not] now expected to be considered by the Treasury in March 2018, are important points of reflection.

When it chooses to proceed with further major steps in the programme the Department should do so having met clear performance criteria agreed in advance. Their failure to do so up to now is a refrain through the IPA’s reports. So too is criticism that UC would have benefitted from better engagement with local authorities. They are critical to the success of UC.

The Government’s approach to major programme assurance is flexible. The IPA agrees with the programme team a distinct timetable and scope for each review. This meant that some important findings on UC were not followed up in detail. Notably, the latest review, which considered the readiness of the digital service for accelerated rollout in late 2017, was explicitly excluded from considering whether previous IPA recommendations had been acted on, whether UC would achieve its business case, and whether it was delivering its policy intent. We were also very surprised that such a major programme has not been subject to the scrutiny of a Programme Assurance Review (PAR) for over two crucial years of its development.

In the eighth year of the programme, a full business case for UC has yet to be submitted. There remains considerable uncertainty about its costs and benefits, not least in its employment impact for claimants other than those in the simplest circumstances. Scrutiny of the programme would benefit from a more transparent approach by the Department. Given its confidence that the programme is on track, the DWP should also benefit from greater openness.

While the UC programme has come a long way since it was reset in 2013, some of its biggest challenges are yet to come.'

And the Office of Budget Responsibility said that 'We conclude that the move to UC is: fiscally significant and complicated to assess; has large, but largely offsetting, effects on spending; involves large gains and losses for some groups; and poses a risk to public spending control due to information gaps'.

The Kakabadse Report ...

Professor Kakabadse's evidence prepared for the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee was delivered in March 2018. Its central (and unsurprising) conclusion was that the personal 'chemistry' between Secretary of State and Permanent Secretary powerfully determines the effectiveness of policy delivery. But it was a well evidenced report and so well worth reading for its fascinating detail. I comment in more detail in Civil Servants, Ministers and Parliament.

... and Brexit

Professor Kakabadse had been particularly concerned to investigate whether civil servants had obstructed Brexit in any way. In a short blog, he summarised his conclusions as follows:-

One key finding of my report is that – contrary to claims and opinion otherwise both in government and/or the media – there is no evidence of bias against Brexit by the Civil Service or civil servants. I found no civil servants who attempted to frustrate or disrupt the Brexit negotiations due to their alleged anti-Brexit or pro-European sentiments.

One Permanent Secretary quoted in my report states, “I think [morale] was very low in the Francis Maude days, but it’s pretty low now. I think a number of things are making it worse at the moment… The default is that we’re to blame for everything. We’re to blame for Brexit being difficult; if we say Brexit’s difficult, we’re blamed for being remoaners.”

Irrespective of the tensions in the civil servant/minister relationship, or being in transition or not, I found no evidence of civil servants deliberately blocking, holding allegiance to the previous government, being deceitful or deliberately misleading the minister, or having an alternative agenda.

Equally, I also found no civil servants who attempted to frustrate or disrupt the Brexit negotiations due to their supposed anti-Brexit and/or pro-European sentiments.

In fact, not only did no evidence emerge that civil servants undermine or thwart their minister or derail the Brexit negotiations but, in fact, civil servants often emerged as dedicated to the Civil Service and their role in serving the public, leading naturally to a positive and productive relationship with their Secretary of State. In so doing, the resilience and impartiality of civil servants is frequently displayed by the great lengths they go to defend and support their minister.

Contrary to media opinion, and worse still for the effectiveness of government, civil servants also described a ‘sadness’ at being an ‘easy target’ unable to ‘defend themselves’, sometimes from those they serve. Indeed, at times, they also felt unprotected by those they serve.

Irrespective of department, my research and emerging evidence highlights that whatever can be done to enable the Secretary of State to realise their Brexit goals and commitments is relentlessly pursued.

This is particularly the case concerning the numerous reports that have been commissioned by ministers on Brexit, future scenarios and the outcomes of negotiations with Michel Barnier and Brussels. The diligence of civil servants through drawing on evidence to make the unbiased and independent case did little to diminish the unwelcome comments thrown at public officials.

Even the integration of different strands of departments into one new entity to pursue Brexit was subject to criticism, “… we work hard on integration, keeping the Minster fully informed and involved, then he calls a meeting and tells us we are lagging behind, we are not pulling our weight. None of us understood why other than this was a political statement which we did not deserve. The sense of betrayal has affected me” (Director General).

Overall, I found no civil servants attempting to frustrate or disrupt the Brexit negotiations. In fact, in the words of one senior civil servant, “it is an insult to even think that.” However, civil servants do nonetheless admit to misunderstandings, misjudgements, feeling inhibited to speak up and, in certain circumstances and with particular Secretaries of State, not knowing how to speak truth to power.

My report concludes that civil servants sincerely work through demanding challenges. But, due to the complexities and misunderstandings in the relationships, certain ministers continue to view civil servants as being negative and undermining.

The Minister and the Official: The Fulcrum of Whitehall Effectiveness

The above-titled PACAC report was published in June 2018, drawing heavily on the Kakabadse Report (see above). Its summary noted that (emphasis added):

- The significance of the minister-official relationship, and the tensions that can arise within it, have long been recognised. Efforts to address this tension, such as the 2012 Civil Service Reform Plan, have tended to focus most on how to make the Civil Service more responsive and more accountable to the ministers they serve. There is much less discussion about the part ministers should play in making minister-official relationships work better.

- Effective planning and prioritisation depends on the strength of the relationship between ministers and their officials. Ministers must be confident that the Civil Service can deliver policies on time and to budget. But officials need to be able to talk to their minister about resource constraints and about realistic timeframes for delivery. Too often, such realism is regarded as resistance or, because the trust is not there, officials feel the conversation is avoided altogether. The need for such honesty and openness about priorities is all the more acute since government has taken on the additional tasks arising from exiting the EU. Single Departmental Plans should be at the heart of these discussions. They have not so far delivered the promised link between the allocation of resources and delivery of priorities.

- ... the most senior officials often lack the subject expertise and depth of experience in the department which their ministers are entitled to expect. The 1968 Fulton Committee lamented what it called the “cult of the generalist”, but the problem has become more serious.

- It is now widely accepted that the closure of the National School for Government has left a gap in [civil servants] learning and development that subsequent provision has failed to fill. Some steps to address this, such as the Civil Service Leadership Academy and the Centre for Public Service Leadership, have been taken. But these and other new institutions will not provide the crucial anchoring role for the Civil Service that the National School for Government did. We intend to look at the possible creation of a new overall body to nurture future talent and leadership in a follow-on inquiry. The Civil Service needs its own institution, where Civil Service thinkers, educators and leaders have the space to reflect on how the Civil Service should be more mindful of itself, its challenges and its future, and which can transmit the values, attitudes and positive behaviours vital to the future strength of the Civil Service from generation to generation.

Single Departmental Plans

The above reference to SDPs is interesting because the government was facing increasing criticism over the vagueness of the public versions of the SDPs, including that they do not link spending plans to priorities. According to Civil Service World, Civil Service Chief Executive John Manzoni told MPs that although the government had worked hard to make versions of the plans available to the public they were “not as good as they should be, but they are getting better each time ... If you look at the internal versions, there is a level of more detail and it does give you the resources. That’s in the good ones; some of them don’t, but most of them do now give you the resources associated with the particular objectives. That is not necessarily down to all the sub-objectives, though in some cases they do.” For example, he said the internal version of the SDP at the Department of Health and Social Care “would be clear what resources [it] has allocated” to public health issues such as obesity, sexual health or tackling alcohol abuse.

Manzoni defended the differing versions following questions from MPs, saying “I believe that if you do all your planning and discussions in public, it becomes a less fruitful exercise”. He added: “It is not as though they are full of state secrets or anything, but some of them might be quite sensitive – they might project workforce losses, or quantification of things that perhaps we do not want in the public domain at that time because they will have an impact. That might be the case, but it also just changes the dynamic of a conversation if you have to do it in public.”

However, IfG senior fellow Martin Wheatley and research intern Tom McGee called on the government to publish much more detail in order to boost transparency.

“The published versions do not show how departments allocate spending to their objectives, so it is impossible to judge what the department has achieved. Manzoni and Bowler claim the internal unpublished plans address this criticism,” they said. “But how can we know? “The lack of transparency contradicts the government’s own stated aim. At the launch of the single departmental plans in 2016 Oliver Letwin, a driving force behind the plans, claimed they would ‘enable the public to see how government is delivering on its commitments’. This is not possible with the published plans. The public is unable to scrutinise how – and how well – its money is being spent by the government.”

John Manzoni's Speech

The civil service's 'Chief Executive' addressed an audience at the Institute for Government in May 2018. His speech contained a progress report on the strengthened role of functional specialists and the consequential need to review the overall governance of the civil service, including how to fund the centre of government including all the new functional leaders and their teams. This will be in tension with the traditional autonomy of individual departments

He also talked about the way the civil service had responded to the challenge of Brexit.

I recommend this former civil servant's perceptive discussion of the capability of the civil service as of late 2017.

Some Sense, At Last, About KPIs

There was much cheering when Prisons Minister Rory Stewart commented as follows on what should be done about filthy prisons full of broken windows:

There is too much saying "We are going to deal with this by setting up a new performance indicator" and "We're going to deduct some money if you don't reach your KPI", rather than spending time on the ground and saying "This is disgusting. Sort it out!".

Success Profiles

John Manzoni launched these in the summer of 2018. An introductory/overview document is here, and there were also detailed descriptions of desired civil service strengths and behaviours.

His aim - laudable enough - was to improve the recruitment and internal promotion of civil servants. The result was typical big organisation stuff - very detailed and probably helpful for inexperienced or nervous recruiters, but arguably over-complex as it expanded common sense into endless charts and detail. Here is one example:

Follow this link to read some sensible advice on leading and managing policy teams.

Windrush

The Windrush scandal that enveloped the Home Office in 2018 drew attention to a profound institutional failure following the introduction of the 'hostile environment' for immigrants - whether or not they had lived in the UK since childhood many decades ago. The austerity-driven downgrading of immigration casework from Executive to Administrative Officers did not help as AOs were not allowed to make significant decisions on their own. "We lost face-to-face interviewing and went to a paper based system." "When you're dealing with thousands of applications, you're not seeing the people, you're seeing the files."

Wendy Williams' Windrush - Lessons Learned Review was punished in 2020 and made sorry reading. Here are a couple of extracts:

- A range of warning signs from inside and outside the Home Office were simply not heeded by officials and ministers. Even when stories of members of the Windrush generation being affected by immigration control started to emerge in the media from 2017 onwards, the department was too slow to react.

- The report identifies the organisational factors in the Home Office which created the operating environment in which these mistakes could be made, including a culture of disbelief and carelessness when dealing with applications, made worse by the status of the Windrush generation, who were failed when they needed help most.

- The lessons are for both ministers and officials in the Home Office to learn. Ministers set the policy and the direction of travel and did not sufficiently question unintended consequences. Officials could and should have done more to examine, consider and explain the impacts of decisions.

- The Home Office demanded an unreasonable level of proof for them to be able to demonstrate their status. At times, staff asked people for evidence for each year that they had lived in the UK (which for the Windrush generation was often over 40 years), and in some cases more than one document. This was clearly excessive, particularly for people applying to confirm the right to be in the UK, rather than applying afresh.

- During my interviews with senior civil servants and former ministers, while some were thoughtful and reflective about the cause of the scandal, some showed ignorance and a lack of understanding of the root causes and a lack of acceptance of the full extent of the injustice done. In addition, some of those that I interviewed when asked about the perception that race might have played a role in the scandal were unimpressively unreflective, focusing on direct discrimination in the form of discriminatory motivation and showing little awareness of the possibility of indirect discrimination or the way in which race, immigration and nationality intersect.

Amber Rudd & Removals Targets

Home Secretary Amber Rudd was poorly served by her officials when (unexpectedly) questioned about immigrant removals targets. She resigned - unnecessarily in my view - but the two officials blamed in the subsequent report by Alex Allan were merely shuffled to other roles.

Jeremy Heywood

After years of heavy smoking, Cabinet Secretary Jeremy Heywood was diagnosed with lung cancer in June 2017 and took a leave of absence from his position in June 2018 owing to his illness. He retired on health grounds on 24 October 2018, and died on 4 November at the age of 56.

Charles Moore wrote a perceptive article about him, and his biography, and his widow (the author). You can read it here.

Subsequent developments in civil service reform are summarised in the next note in this series.