This note summarises developments from July 2019 - when Boris Johnson became Prime Minister promising that the UK would leave the EU on 31 October - "no 'ifs', no 'buts'". Earlier notes in this series are listed here.

There had been numerous suggestions, in the previous weeks and months, that the civil service would be shaken up in some way. Ardent Brexiteers blamed the civil service for the previous government's failure to strike a Brexit deal acceptable to parliament, and suggested that 'heads should roll'. In the event, several officials closely associated with the Brexit negotiations and preparations announced that they would leave the civil service during the summer, thus defusing much of the possible tension. And Prime Minister Johnson decided to retain the services of Cabinet Secretary Mark Sedwill, for the moment at least.

But eyebrows were raised by Mr Johnson's decision to recruit Dominic Cummings as a senior adviser in No.10. Civil Service World reported as follows:

Dominic Cummings, the incoming senior adviser to prime minister Boris Johnson, has called the concept of a permanent civil service “an idea for history books” and proposed the abolition of the role of permanent secretaries in his vision for civil service reform.

Cummings, a former special advisor to Michael Gove in the Department for Education who then went onto lead the Vote Leave Brexit campaign in 2016, is a longstanding critic of the organisation of Whitehall. Following his exit from government, he has set out his criticism and proposals for changes in Whitehall on his blog, building on reforms he set out in a talk for the IPPR think tank in 2014 entitled The Hollow Men: What's wrong with Westminster and Whitehall, and what to do about it.

Permanent civil service 'an idea for the history books'

A lot of problems with the civil service stem from the incentives for promotion in departments, Cummings said in his 2014 talk, which hit out at both HR practices across government and its ability to deliver policy. He said the system is bound to “create crises and frequent spectacular failures” and that he wanted to end the principle of a permanent civil service. “The people who are promoted tend to be the people who protect the system and don’t rock the boat,” he said. “A lot of young people who care and work hard are often disillusioned quite quickly and leave, and the ones who play the system and focus on personal goals and not the public interest also tend to be the ones who are promoted . “It promotes people who focus on being important, not getting important things done, and it ruthlessly weeds out people who are dissenters, who are maverick and who have a different point of view.” This means that civil servants do not have the skills to tackle big problems, which ministers cannot change due to recruitment rules, he said. “So if you have an entire political structure that selects against the skills of entrepreneurs and successful scientists, don’t be surprised when the people in charge can’t solve problems like entrepreneurs and scientists.”

He said that in organisations that work very well, there are “people that care, they try hard”, but “in large parts of the civil service, the whole HR system encourages the opposite”. “Almost no one is ever fired,” he said. “Time after time after time, I would be in the [education] department and on a TV screen it would say ‘Latest Gove disaster, Gove botches X’, and I would look through the glass screen and you would see the official responsible for it the lift, pottering home at 3.30 in the afternoon, doesn’t care. Why not? Because failure is normal, it is not something to be avoided.”

In comments that mirrored Michael Gove’s reported criticisms of flexible working arrangements, Cummings claimed that the DfE had to ban major announcements on Mondays “because you can’t assemble a team reliably on a Friday”. “Between flexible hours, compressed hours and a culture that says it's perfectly acceptable to go on holiday the day before an announcement you’ve been working on for the last six months, it is very hard to get everyone in the same room. So we just had to ban announcements on Monday, because we knew it would all just fall apart.”

He said the “huge system in Whitehall, in my opinion, is programmed to go wrong, it can’t work”, and civil servants lacked basic skills. He said when he had first arrived at DfE with Gove in 2010, "every budget you got would be wrong, every contract process would go wrong, every procurement will blow up in your face and legal advice will probably be wrong", although conditions improved from 2012. “If you can’t procure things in your own building effectively, what are the odds you can procure things for 20,000 schools? The odds are very small, and that is why you see the same cycle constantly of: why did this go wrong? Well, so-and-so signed a duff contact but then so-and-so moved, and the person in charge says, 'Well it isn’t my fault, I wasn’t there then, I’ve taken over this process'. He said telling officials that he wanted to pursue the civil servant who had been responsible for a project that had gone wrong would prompt "shocked faces in Whitehall". "Their reaction is: ‘Oh my god, Dom, you can’t do that, if you did that where would it end?’ Which just about sums it up.”

He said there was a need to “re-orient” Whitehall to what he said should be the national goal of making Britain the global leader in education and science.

“We need to bin some institutions and create others... We need to reorient Whitehall to think about to how to incentivise goals, not micro-manage methods."

Chief among his plans was to “end the concept of the permanent civil service in general". "I think it is an idea for the history books [and] In particular, I would get rid of permanent secretaries," he said. “At the moment, the permanent secretary has a role that is a combination of chief policy adviser, department CEO and a fixer, and it is a crazy combination. It is mis-defining the role. "What we should have is a chief policy officer for the department, and it would be good to have a very small team that fulfils that role – preserves institutional memory, runs proper libraries and maintains proper records. But this role should have no responsibility for management and implementing... and move all of the idea of a CEO [chief executive officer] or a COO [chief operating officer] of the organisation to a completely different position.” He said that such change would be possible because of so-called “beneficial crisis”.

Cummings, who led the campaign group against Britain’s membership of the Euro, said: “People will say it's impossible to do this, but people have told me too, 'You’ll never beat Blair on the Euro, you’ll never get more than fraction of your crazy plans through the DfE'. Things are possible, particularly when crisis hits."

Speaking two years before the 2016 referendum on EU membership, he added: "The EU was created on the basis of what they call beneficial crisis, and because of the nature of the world and the way things are going we’re going to see lots of beneficial crisis shortly, that would enable us to change things along the lines I’ve suggested if we want to.”

Ministerial appointments

In comments that were noteworthy in light of Johnson’s reshuffle yesterday, Cummings said that there was a need to radically slim down the Cabinet. (The reshuffle created a 22-strong cabinet, with a further 10 ministers able to attend.) “You have to shrink the cabinet,” Cummings said in 2014. “The idea of a Cabinet of over 30 people is a complete farce; it should be maximum of probably six or seven people.”

Comment Quite a few civil servants will share Mr Cummings frustration with performance of the government machine. Some of his criticisms were clearly misplaced; very few senior officials leave their desks at 3.30. Most of them work very long hours. But flexible working - especially for female staff - can cause problems around weekends, and the Senior Civil Service certainly tolerates poor performance far too easily. It is also true that mavericks, entrepreneurs and scientists are seldom promoted to the highest levels - but this is partly because Ministers themselves too often prefer to be surrounded by courtiers and 'yes men' rather than tough independent thinkers. Indeed, Mr Johnson made it clear that everyone in his first Cabinet had to support a hard Brexit if there were no other way of leaving the EU on 31 October. Those Cabinet Ministers would in turn no doubt expect to be enthusiastically supported by their senior officials.

After a little reflection, I published this blog in August 2019:

Dominic Cummings & the Civil Service

Dominic Cummings’ arrival in No. 10 is said to be very bad news for the civil service. I am not so sure. If you dig a little deeper, according to Oliver Wright:

[Dominic Cummings] at the Dept for Education inspired extraordinary loyalty, certainly among fellow believers but also from some civil servants who were as frustrated by Whitehall bureaucracy as they were. As one person in the [Education] department put it: “The caricature of Dom as the villain is wrong. He accepted argument and evidence. He wasn’t dogmatic. And a lot of senior civil servants responded to it as a breath of fresh air. When he fell out with people it was over whether things could be done differently.” Another former colleague said that he had never worked for someone “more inspiring or oddly charismatic”.

David Alan Green commented as follows:

[Dominic Cummings’] candour and openness was striking. … There is none of the platitudes and evasions of the politicians of both sides on Brexit.

Looking forward, many would surely applaud Mr Cummings’ reported wish to foment a cultural revolution in Whitehall so that civil servants (and Ministers) have a more instinctive grasp of the importance of science, technology and productivity for the UK’s future. And I suspect that a majority of civil servants would share some or all of Mr Cummings’ reported criticisms of the Whitehall machine:

- its inability to respond quickly to errors;

- the “slow, confused” and usually non-existent feedback;

- the “priority movers” system that sees incompetent staff members (“dead souls”) moved into jobs elsewhere in the civil service rather than sacked; and

- the “flexi-time” working regimes that allow key personnel missing in action when big announcements need to be planned.

It is not as though the UK has a great track record in policy making. There have been lengthy analyses of government blunders for which politicians must take a large share of the blame. There are very few senior politicians who are nowadays genuinely keen on prioritising sensible policy-making, nor science, technology and productivity. Indeed, it is interesting that previous Cabinet Ministers seem to have detested the obsessive Dominic Cummings and his criticisms. David Cameron called him a career psychopath and Nick Clegg said he was loopy. Theresa May’s views are not known, though we do know that Mr Cummings thought that her triggering of Article 50 was premature, and that her implementation of Brexit in general, and her red lines in particular, were catastrophically inept. Few civil servants would disagree.

The Mandarinate must nevertheless surely also take much of the blame for the UK’s current woes. It is hardly entirely their fault, but they have not shown themselves to be effective in speaking truth to power when it was most needed.

Sadly, I doubt that Mr Cummings has identified the right medicine to cure the ills that he has identified. He has argued, I understand, that “quitting the EU will sweep away another roadblock on the path to his vision of the UK.” But I cannot understand that logic whether it comes to encouraging revolution in Whitehall or elsewhere. It would be much better – if less exciting – to carry out a root and branch review of the relationship between Parliament, Ministers and the civil service – a 21st Century Haldane Report, if you like.

Short of that, so far as the civil service is concerned, I suspect that part of the answer will need to be better targeted performance management. I was struck by this Matthew Parris anecdote, which applied just as much outside the FCO as within it:

… our outgoing ambassador remarked that, beyond all the routine work that had had to be done day-in day-out, he reckoned he had offered important advice at critical moments … on perhaps a dozen occasions. On many of these his advice had been good, as events had shown. A handful of times, however, subsequent events had proved him wrong. … [he] did not suppose [anyone in the FCIO] had ever noticed, let alone recorded, the score. Nobody would have cared if he had always been wrong, and nobody but himself would have known if he had always been right. [His] progress had therefore depended on his competence in the immediately noticeable things – in everything [but whether he had given] what would later turn out to be the right advice.

This happened a good while ago, of course, but not much has changed over recent years. We still mainly promote club-able ‘good chaps’ (and female chaps) who are brilliant courtiers and fixers and who don’t startle any horses. It would be difficult, but not impossible, to change the system, and it would need serious political will. Maybe, just maybe, Dominic Cummings will provide the necessary pressure?

There is plenty more about Dominic Cummings in the Special Adviser section of this website, and here in particular.

The Civil Service and Brexit

Keen Brexiteers firmly believed that the senior civil service had been trying to scupper Brexit following the 2016 referendum. After the arrival of the Johnson government, however, keen Remainers became concerned that civil servants had become too willing to promote Brexit ‘propaganda’. The key change was is that civil servants were – in some ways – finding it much easier to work with the Johnson government that with its predecessor.

Keen Brexiteers firmly believed that the senior civil service had been trying to scupper Brexit following the 2016 referendum. After the arrival of the Johnson government, however, keen Remainers became concerned that civil servants had become too willing to promote Brexit ‘propaganda’. The key change was is that civil servants were – in some ways – finding it much easier to work with the Johnson government that with its predecessor.

Prior to 24 July 2019, it was far from clear when the UK was intended to leave the EU, nor on what terms. The Cabinet was badly split and there was in particular zero clarity about whether ‘No Deal’ was a realistic outcome. Officials were roundly criticised for being insufficiently wedded to the Brexit project, whereas the truth was that they were still giving advice (which undoubtedly included worries about ‘No Deal in particular) and were also reflecting the different messages coming from different Cabinet Ministers.

Once Mrs May had gone, it became much easier. The government’s policy was clear. All Ministers now said that Brexit was a good thing, and that the UK needed to plan and prepare to leave on 31 October with or without a deal. Civil servants could then enthusiastically promote those policies, whatever their private misgivings. The only constraints were that civil servants could not communicate untruths, nor criticise political opponents.

More Generally ...

Ministers' faith in officials took a knock after Home Secretary Amber Rudd was poorly supported during and after questioning in the House of Commons re immigration targets. Alex Allen's subsequent report also criticised poor communication between Spads and officials. On the other hand ...

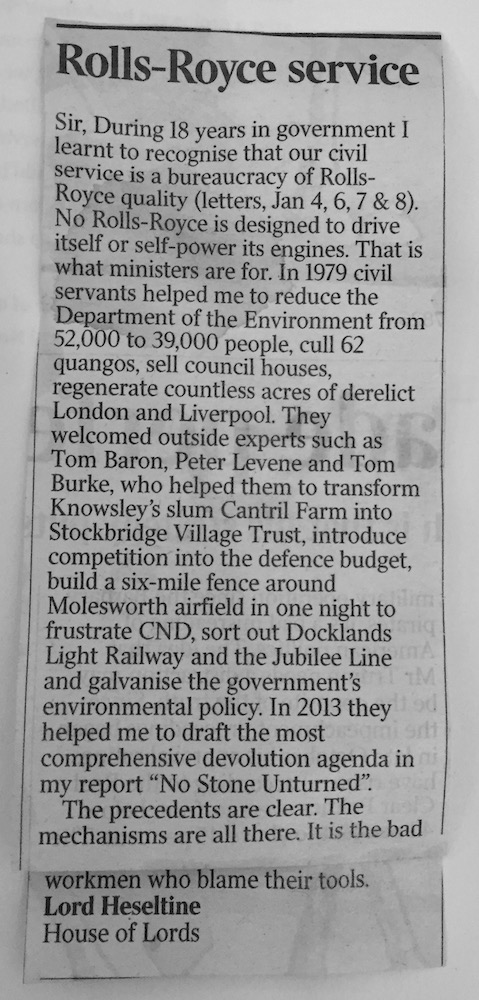

... Lord [Michael] Heseltine wrote to The Times with this strong defence of the civil service, and criticism of current Ministers, in January 2020.

Newly appointed Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced, in his March Budget, that he intended to move 22,000 civil servants out of London by 2030, beginning with the creation of an economic campus in the north of England. The campus would be staffed by around 750 officials from departments including the Treasury, the Department for International Trade, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, and the Ministry of Housing, Communicates and Local Government. It remains to be seen, if course, whether his plans will survive the distractions of tackling Brexit implementation and the post-COVID-19 recession.

Civil Service Impartiality

There is little doubt that the majority of the senior civil service will have voted to 'remain' in the 2016 Brexit referendum, and will have found it difficult to support ministers during the next few months as the latter appeared incapable of developing any coherent description of their desired future relationship with the EU. However, as noted above, once the destination became clearer most officials seem to have relished the challenge of making Brexit work. Cabinet Secretary Mark Sedwill commented as follows in February 2020:

It’s frustrating, but we can’t be completely immune from the wider public and political debate. One of the things I said in a message across the Civil Service was that Brexit is a polarising issue. That is a fact. It’s not like other political issues. It wasn’t that people agreed or disagreed about, say, the role of the state in the economy, where people have lots of different views. It was a binary proposition. And, as I said at the time, civil servants, as citizens, weren’t immune from that.

Inevitably, every institution was being drawn into the debate. It would have been virtually impossible for the Civil Service – particularly in Whitehall – when the country’s going through something that significant, and the political temperature is that high, not to find ourselves drawn in – even if we didn’t step into the debate ourselves.

However, I do believe the wider Civil Service was largely immune from it. Whitehall is probably only 10% of the Civil Service organisation.

It is frustrating to hear civil servants’ impartiality being questioned, because I simply don’t think it’s true. I genuinely don’t know – and don’t need to know – how civil servants voted in the referendum. Some of our most talented people, at all grades, of all ages, from all parts of the country, absolutely threw themselves into the Brexit project, supporting the Government and delivering its policy, whether it was in DExEU, in the teams in the Cabinet Office, or now in the teams in No.10. So, in the end you think, well, that’s what’s real and important.

Renewable Heat Incentive Inquiry

This Northern Irish incentive scheme was intended to ensure that 4% of Northern Ireland's heat consumption would come from renewable sources by 2015, with that figure increasing to 10% by 2020. The scheme offered to subsidise the cost of its claimants' fuel - mostly wood pellets - for running their heating systems. But the fuel actually cost far less than the subsidy they were receiving, effectively meaning that users could earn more money by burning more fuel. A whistleblower contacted Northern Ireland's first and deputy first ministers in January 2016 to allege that the RHI scheme was being abused. One of the claims they made was that a farmer was aiming to collect about £1m over 20 years for heating an empty shed. It was also alleged that large factories that had not previously been heated were using the scheme to install boilers with the intention of running them around the clock to collect about £1.5m over 20 years. Successful applicants to the RHI scheme are continuing to receive payments because they agreed contracts with the government for the 20-year lifetime of the scheme. As a result, more than £1bn of public money is due to be paid out to claimants over 20 years.

The subsequent inquiry exposed horrendous failings in both Whitehall and Northern Ireland. The Chairman's Statement is here - see para 38 (sub-paras 2, 8, 13, 14, 16-19, and 31/2) in particular.

The Chairman's comment that "[The scheme's features] together made the scheme highly risky, yet the risks were not properly understood ... within the Northern Ireland Government" echoes the long held view of the National Audit Office that civil servants are not risk averse but they too often do not understand the risks attached to what they want to do.

>>>>>>>>>>

Subsequent civil service reform activity is summarised here.