This note summarises developments in 2023.

Simon Case

The year began with the publication of a very unflattering portrait of Cabinet Secretary Simon Case.

A few months later, eminent political historian Sir Anthony Seldon co-authored Johnson at 10: The Inside Story which heavily criticised both the former Prime Minister and Simon Case. In an interview with The Times, Sir Anthony said “I believe that the civil service has never been weaker, more demoralised or less powerfully led. The country needs a strong effective Whitehall, as recent policy failures and errors show. The civil service is a team without a captain. It is crying out for modernisation and change, but the head of the civil service lacks the authority or the experience to do it. ... With great sadness, because Case has been an exceptional public servant, I have concluded that the time has come to release him for a fresh leader charged with guiding, modernising and reforming the civil service, and providing renewed grip as cabinet secretary.” A permanent secretary added: “I’ve never thought Simon was the right person to run the civil service. He doesn’t have sufficient experience and the problem with Whitehall is that it operates too much like a court, and Simon is about the most extreme example of a courtier you can find.” Another senior official, referencing 'partygate', said of Case: “There is a view that the person at the top isn’t going to fight for what’s right and that is a potentially fatal reputational blow.”

Sam Freedman published an excellent blog in June 2023 setting Simon Case' appointment within a history of the decline in Cabinet Secretaries' influence since the 1980s. Here are some excerpts:

[Simon Case] has been hapless. I have been interviewing numerous ex-senior civil servants for my book and the unanimous contempt for Case is quite something. It’s shared by the current cadre of permanent secretaries too. The general consensus is that he only has the post because Cummings considered him biddable. He doesn’t have anywhere near the requisite experience, having never been a permanent secretary in any department. Despite that many were initially prepared to give him the benefit of the doubt, but as one former official said to me: “the way he's gone about means he’s lost the room”.

The main complaint is that he acts as a courtier within No. 10, rather than upholding the integrity of government. Instead of taking on politicians as and when necessary, he refrains from difficult conversations and offering advice they might not want to hear. This really matters. The Prime Minister of the day needs to hear those messages, or we end up with the omni-scandals of the past few years. But also because the Cabinet Secretary is head of the civil service. ...

Things started to change under Margaret Thatcher, as she side-lined the rest of cabinet and increasingly directed the business of government herself with an handful of advisers. But her Cabinet Secretaries, Robert Armstrong and Robin Butler, largely managed to hold the balance, intervening when they felt her behaviour was inappropriate, and defending the civil service when necessary. They were the last of the old guard.

... the role of Cabinet Secretary was now tied too closely to the Prime Minister of the day. [Mark] Sedwill was seen as an enabler of May rather than a balancer. As her reputation in the Tory party sank through the months of the Brexit deal drama, so did his. The Brexiteers backers of a Johnson leadership were briefing against him. The role had been irredeemably politicised. ...

[Simon Case] has, like his two predecessors, focused on advising and supporting the Prime Minister. The civil service as an institution has been left leaderless. When Johnson’s first adviser on ministerial standards, Alex Allan, concluded that Priti Patel had bullied a permanent secretary to the point where he quit, the Prime Minister simply ignored his advice. Allan resigned. Previous Cabinet Secretaries would have fought this decision, as it severely undermined the senior civil service. Case does not appear to have done so. He has left multiple issues of integrity alone in order to keep the support of the Prime Minister, whether Johnson, Truss or Sunak.

No doubt inexperience and character matter here. But this behaviour is also the endpoint of a long-term erosion in the balance of the Cabinet Secretary role: between representing the cabinet and civil service versus being an aide to the Prime Minister. This was symbolised by Case taking a desk in Number 10, rather than on the other side of the connecting door to the Cabinet Office. The wonderfully named Burke Trend, who was Cabinet Secretary in the 60s and 70s, emphasised the importance of this balance in doing the job well: “The Cabinet Secretary is not the Prime Minister’s exclusive servant…there has to be a central official that the machine can come around…He has to be a bit more detached”. In a world where cabinet government no longer meaningfully exists, this is probably no longer possible. Which leaves the rest of Whitehall defenceless and looking for other routes to raise their concerns.

Simon Case himself had an opportunity to recognise recent and current threats to good government - and address his critics - when he delivered his second annual lecture in February 2023, but he chose to avoid any sign of controversy, let alone confrontation. Here, for instance, are his 'five tests' to 'help assess how our institutions are doing', all of which are so sensible by anodyne that they could have been suggested by any of his predecessors

The first one - do we know who our customers are? And do we serve them well? Are we delivering what our elected representatives ask of us, on behalf of the voter and the taxpayer? Have we really taken the time to understand who we work for and what they want?

Second - are we staying true to our core purpose? Even as we do that necessary modernising, are we staying true to our roots?

Third - are we updating the way we do things to stay relevant? Are we adopting new technologies, systems and processes so that we can solve problems and deliver public services in the way that 21st century citizens would want?

Fourth – is our approach to managing risk proportionate? Have we got the balancing act right? In a fast-changing world, are we neither too cautious, nor too reckless?

And the fifth and final test – do we have the right people in the right places? Without that, we would never make progress on the first four tests.

Matthew Rycroft

Jess Bowie's interview with the Home Office Permanent Secretary is of some interest. He succeeded Philip Rutnam who had accused the Home Secretary of bullying - and Sir Matthew had shown himself willing to defend unfairly criticised colleagues. But his generally diplomatic and optimistic answers nevertheless included many confessions that he and his department still had "a good way to go".

Sue Gray

Sue Gray, the author of the Partygate report, resigned from the civil service and announced that, subject to ACOBA approval, she was to join the office of Keir Starmer, Leader of the Opposition and likely next Prime Minister. Many criticised this decision, not least on the grounds that she would in due course be able to draw on her knowledge of Conservative ministers policies, practices and characters when advising Sir Keir. But this was something to be considered by ACOBA and it was pointed out than many previous senior officials had "become" politicians including David Frost, Dominic Raab, Victoria Prentis, Valerie Vaz, Jonathan Powell, Andrew Lansley, Helen Goodman, James Sassoon and Keir Starmer himself. There was also no evidence that Ms Gray had ever been anything other than impartial in advising Conservative ministers, and many thought that she had if anything been very gentle in her Partygate report. A lot of senior officials (and I) nevertheless regretted that she had decided to work for the Labour party as here decision looked bad, whatever its justification, rights and wrongs.

ACOBA subsequently cleared Ms Gray to work for the Labour Party as long as she waited for 6 months after leaving the Civil Service and made it clear that, from their point of view, she had behaved entirely properly.

Ministers told Parliament that there was 'prima facie' grounds for believing that she had breached the Civil Service Code on the grounds that she had not declared "an outside interest" to her line manager. I and others pointed out that no employer, in the private or public sector, expected their employees to reveal that they might in future be offered a job - for instance by a competitor.

Dominic Raab

Adam Tolley's report into allegations that Dominic Raab had bullied his civil servants led to Mr Raab's resignation in April 2023. Further comment and analysis is here.

Retained EU Law Bill

Crazy promises in last year's Conservative Party leadership elections had led to the deadline in this draft legislation (which required 4000+ pieces of ex-EU legislation to be reviewed) to be brought forward from 2026 to the end of 2023. To the surprise of no-one sensible, this deadline was dropped in May 2023, but ministers blamed the civil service. The FT's Peter Foster commented as follows:

Two cheers this week for the UK government bowing to the inevitable and announcing that it is rowing back on significant parts of the madcap retained EU law bill, which originally sought to “review or revoke” almost 5,000 pieces of EU-era legislation by the end of the year.

As widely predicted ... the government dropped the much-maligned “sunset clause” that risked EU-era laws just falling off the statute book by accident if they had not been actively saved by ministers.

This reboot is a partial step forward. On the upside, it turns the original Reul bill’s underlying assumption on its head — EU-era law is now automatically preserved unless it is actively revoked, not vice versa — which is just plain common sense.

I say only “two cheers” because the U-turn came via a particularly graceless attack on the civil service by the business secretary Kemi Badenoch.

She used an article in the Daily Telegraph to blame Whitehall departments for the original bill’s failure because, she wrote, they had focused on “which laws should be preserved ahead of the deadline, rather than pursuing the meaningful reform government and businesses want to see”.

The newspaper duly took the bait and, egged on by the bill’s original proponent, Jacob Rees-Mogg, obliged with a headline telling its readers that “Whitehall ‘blob’ halts repeal of Brexit laws”.

There is so much that is wrong with this and Badenoch’s statement, aside from the obvious point that it’s immensely damaging when ministers use the civil service as a shield for their own mistakes and as a political football in the Brexit wars — all while repeatedly accusing the civil service of being political!

The fact that civil servants were trying to preserve legal continuity and avoid the creation of unexpected legal vacuums points precisely to why the Reul bill was so obviously deeply flawed, as has been clear for a very long time.

Without apparent irony, Badenoch co-opted “businesses” to her cause by accusing the civil service of blocking the “meaningful reform ... business wants to see”, when in truth the U-turn has been forced on the government precisely because business wanted nothing to do with the bill as originally conceived.

Dmitry Grozoubinski explained the problem with the legislation in this Twitter thread:

1/ Treating this [criticism of the civil service] in good faith because I can appreciate how someone may intuitively wonder [why a well-resourced team could not manage to review 18 laws a day until the end of this year].

To begin with, no matter how large a civil service team you put together, it's not going to contain expertise on the technical detail of everything 4,000 laws cover.2/ So what does examining a law actually involve. Let's pick an EU directive at random - this one is on the reduction of single use plastics. So your first step would probably be to find someone in the civil service who actually knows about this...

3/ But they're not enough. Not really. Not to make a big decision like whether to scrap the law or not. You'd want to consult with environmental experts, presumably to see if the law is working as intended, and what a repeal might mean ... but that's not enough either.

4/ What are the implications for business? Think about all the businesses that make things with plastic packaging. Now think of all the businesses that sell them. What are the export implications? There are many foreign markets, all different, and the impacts may vary.

5/ The directive requires a good bit of record keeping and data collection. Does anyone in the government use that data? Will they miss it? Can it be replicated?

6/ Then there are the legal applications. How many regulatory decisions and procedures derive their authority from the Act? How does the Act interact with other Acts? How is it accounted for in the budget?

7/ None of these questions are insurmountable. The answers ARE out there - but the vast majority of them aren't at the fingertips of your civil service scrap EU taskforce, or require expertise or input they don't possess.

8/ Making matters harder, there isn't a comprehensive database anywhere in government with a list of all possible stakeholders on every imaginable issue. Even finding the right person inside the bureaucracy to help you start looking can be time consuming.

9/ Finally, what happens when inevitably there are differing views within government and among stakeholders about whether a law should stay or go? Are you going to empower your civil servants to make line ball calls between different industry groups? Between competing interests?

10/ Even if you are, any senior civil servant empowered to make that call is going to want to hear a comprehensive case for and against, consider the recommendations, perhaps seek supplementary data or additional views. Time time time.

11/ Throwing more bodies at the problem may help mitigate some of the above issues, but unfortunately not all of them. Inevitably, trying to review 18 different laws a day is going to cause bottlenecks, and stakeholder consultations take time even if you're well resourced.

12/ So yeah, I completely understand why intuitively this seems like it wouldn't be that hard or that you could solve it by throwing more fast streamers at the problem. Unfortunately I think it is ... and you can't.

A good deal of government business seemed to have been conducted over WhatsApp in recent years. It was therefore good to see that one public release of Whats App chats included this from Defence Secretary Ben Wallace

“This is the defence secretary. I am not entirely sure why I have been put on the chat. Nor do I suspect has anyone else. I shall continue to do things via [Private Offices] and speaking directly with your boss. “

The Blob

I enjoyed this May 2023 article by Lord (Daniel) Finkelstein

A friend of mine was working as an employment lawyer a few years back when he was approached by a very plausible man who wanted his help in taking action against Boots, the chemist, for wrongful dismissal.

The man’s tale did, indeed, seem actionable. My friend organised a second meeting and noted down all he was told. Then, as he was bringing matters to a conclusion, his new client said he had one more thing to add.

“They are following me,” he said. My friend was startled. “What do you mean, ‘They are following you’? Who is? Boots?”

Yes, Boots, replied the client. “I see them everywhere. With their plastic bags.”

I am reminded of my lawyer friend every time I hear Conservatives talk about “the Blob” and how it is frustrating their political intent. For there was a time when such talk was plausible and actionable — only for it to become a deeply eccentric conspiracy theory.

In 1987 William Bennett, Ronald Reagan’s education secretary, spoke at a news conference about the way the educational bureaucracy — the bit of the system that was not teachers — kept growing. He lamented the expense, wondering whether so many people were really needed. And he called this bureaucracy “the Blob”.

He was making reference to a 1958 science-fiction film that starred Steve McQueen in his first leading role. The Blob was a large, jelly-like creature that landed from space, consuming everything in its path, and with every person or, indeed, town it consumed, the Blob would grow.

Bill Bennett is an important figure in the US conservative movement and Michael Gove a keen student of American conservatism, so perhaps it is not surprising that when Gove became education secretary he borrowed Bennett’s language. With a slight twist. Bennett’s original observation was about the Blob’s size and ability to grow. Indeed, that’s why he chose the metaphor. Gove put more emphasis on its political outlook. The Blob, as he saw it, was a shapeless shifting obstacle to reform.

However much licence Gove was taking with the film reference, the idea that there was institutional resistance to his reforms did make some sense. Institutions and groups do have cultures and tenacious positions that are resistant to change. That is why it has always been wrong to argue that there is no such thing as “institutional racism” or that there was no such thing as society, only individuals and their families.

Gove was at least arguing for certain specific and workable policies (even if contestable) and was taking responsibility for advancing those policies. And he was using a metaphor with a history in the field of education and a clear meaning.

But it appears we have now reached the Boots carrier-bag stage of this originally plausible argument, for “the Blob” is now everywhere to be found in Conservative argument, eating everything in its path, including common sense.

There is a paranoid strand of socialist thinking that believes the civil service and the capitalists and the bankers (and, according to taste, the Zionists) form a permanent government that has to be destroyed before any sort of change is possible. It is the resistance of this establishment that explains the failure to achieve socialism, rather than socialism’s own glaring flaws.

Now this sort of thinking — best left to the Bennites — features strongly on the right. It is the civil service and lawyers and “activists” and the EU and people with degrees and people who live in cities (and you, if I understood the last couple of days of Tory debate properly, because you aren’t having enough children). This is the Blob. And the Blob is to blame for everything. There’s no point saying the Tories, being in power, should have solved this or that problem. Because the Tories aren’t in power, you see. The Blob is.

This is how the home secretary gets to make big platform speeches criticising the policies and lack of achievement of the home secretary.

The Blob has been cited as stopping the government from preventing illegal migration in small boats; the Blob did in Dominic Raab; the Blob forced Kemi Badenoch to change course on EU legislation. The Blob has appeared in speeches, in comments to newspapers, in headlines, in parliament and in letters to party members appealing for their support with an attack on the government’s own employees.

The Blob has become an all-purpose conspiracy theory in which vague and sinister forces — “them” — are acting together to frustrate the brave reforms of Tory ministers.

It is fitting that the metaphor was drawn from a science-fiction movie because the Blob is an escape from reality. The reason that the Retained EU Law Bill had to be changed was not, as Jacob Rees-Mogg has alleged, because of the indolence of the civil service and the resistance of the Blob. It is because the bill’s original idea that all the retained law could be disposed of by the end of this year was reckless, foolish nonsense.

When describing that idea, a better film reference than The Blob would have been Dumb and Dumber.

Just as “real socialism” has never been tried because the bourgeoisie prevent it, so “real Brexit” hasn’t been tried because it has been stopped by the Blob. In this way, Brexit remains always just over the hill, requiring one more campaign to achieve. But if you ever get over the hill, you know who will be there when you arrive? The Blob.

The Blob is not only a flight from reality but also a flight from responsibility. Because the Blob is too big, too powerful, too hungry ever to be defeated. So no failure can ever be your fault. You tried your best but it was the Blob, you see. Blame “them”.

And it is a flight from leadership. Governments will always face some resistance to their programmes from vested interests and those who are set in their ways. And it will always have to work through institutions with their own history and culture. Leadership is about finding practical ways forward, taking your staff with you, working with existing interests, using persuasion and, where necessary, a bit of push.

To blame your own workers, public servants who work for you and whom you are supposed to manage — people whose welfare and output are your responsibility — is disgraceful. To argue that there is some vague jelly-like substance that makes progress impossible is defeatist. And also fundamentally untrue, as countless successful ministers have shown. Gove certainly did not think progress impossible.

The Blob is the language of protest, not of government. It is the language of opposition. And that is where it is taking those people who use it.

David Gauke

Addressing the First Division Association (the FDA - the senior officials' trade union) former minister David Gauke echoed much of the above analysis. Here is an extract from the FDA's report of the speech:

Gauke added "It also pains me to see that relationships between ministers and officials have become more contentious in recent years. There are many ministers who speak very highly of officials and officials who speak very highly of ministers, or at least some of them. But we all know that there are some specific controversies and behind that a wider criticism of the civil service that is obstructive and has failed to implement the agenda of government."

The former Lord Chancellor outlined criticisms such as these as " an example of people - sometimes ministers, sometimes journalists - refusing to address complex situations and coming up with simple answers as to why simple promises cannot be fulfilled when confronted by reality. The blame gets put on ' the BLOB' or the out-of-touch elite and for these purposes, this is capital letters [senior civil servants].

Gauke called this " wrong for two reasons - a refusal to accept complexity and the need for trade-offs ... and second, ministers have to take responsibility for they are the ones who make decisions. When it comes to negotiating the terms of our exit from the EU, our immigration policy or post-Brexit regulation, it is ministers who decide and ministers who should be taken to account."

On Brexit, he called it " a source of much wishful thinking and failure to engage in the details by politician", adding "I think there is a remarkable correlation between those who fail to understand the details and those who have been most critical of the civil service". Gauke described it as " just one example of the electorate being provided with great promise of what could be delivered, with little idea of the practicalities or how to deliver them". He referred to " levelling up as another example, where politicians raised expectations without understanding whether those expectations were deliverable".

He outlined the problem as "politicians who have spent a lifetime ignoring the details and complexities, who see policy issues as primarily a way of asserting an identity or winding up opponents, or advancing themselves within their own party, rather than means of solving problems. Without focusing on any one individual, I can tell you it is much easier to write columns about government policy than to devise and implement one. Better that politicians become columnists than columnists become politicians."

Non-Executives

The Public Administration Select Committee published an interesting report in June 2023 drawing attention to numerous problems associated with the appointment and use of non-execs on Departmental Boards.

Targets, Plans, Outcomes

Organisations, including governments, are very unlikely to succeed if they don't plan how to meet their objectives - and then review those plans and adapt them as necessary. But politicians unfortunately find that the uncertainties of government make target setting very risky, and reporting against targets even more risky still.

Prime Minister Tony Blair, for instance, announced that he would publish annual reports on civil service reform, but in the event only one report was published.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak had announced 'five priorities' in January 2023:- "I fully expect you to hold my government and I to account on delivering those goals". The IfG's Hannah White was far from alone in arguing that the PM had" set himself a deliberately low bar – while ducking challenges that need addressing later". But it later turned out that most if not all of these goals would not be met.

And then, in July 2023:

'Ministers’ decision to again block the publication of outcome delivery plans is “surprising and disappointing”, Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs chair William Wragg has said. Wragg said ministers’ argument that this would enable departments to focus on Rishi Sunak’s five priorities – halving inflation, growing the economy , reducing national debt, cutting NHS waiting lists, and stopping small-boat crossings – is “wholly unconvincing”.

ODPs help departments to measure their performance against key priorities. Summaries for the first round of annual plans, for 2021-22, were published in July 2021 but none have been made publicly available since.

HM Treasury and Cabinet Office ministers John Glen and Jeremy Quin wrote a letter to the PACAC chair earlier this month, saying departments “will only be required to produce internal ODPs for 2023-2.'

Populism

Janen Ganesh made an interesting point in an article in July 2023. The rise of populism on both sides of the Atlantic, and elsewhere in the world, presents its supporters with an irony or conundrum:- Populism sets itself against the elite and deep state but requires the state to become more powerful and protectionist: dispensing subsidies, guiding favoured sectors, and curbing free trade.

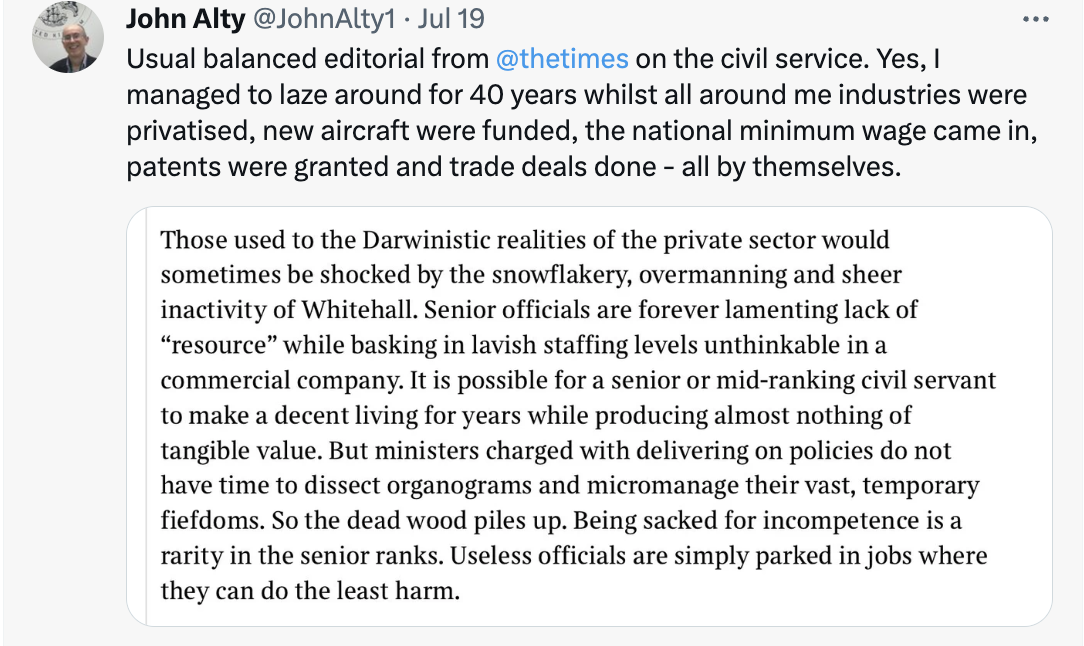

Meanwhile, nearer home, there was a steady stream of anti-civil service reporting and comment in parts of the media. I rather enjoyed this repost from a retired official:

The British State

Despite the constant attacks on the civil service, there was in some quarters a growing realisation that there might be fundamental problems with the nature of the British state. Nick Tyrone, for instance, commented in 2023 that:

'Britain is fundamentally poorly governed ... The current government wants to blame this on the civil service, but that's projection ... The vast majority of the dysfunction comes, sadly, from our elected officials ... This isn't a partisan point I'm making either. Labour governments tend to be just as bad as Tory ones.'

His full article is here.

Breaking Down the Barriers

The above named report by Reform (subtitled Why Whitehall is so hard to reform) was published in July 2023. You can read it here.

I published this blog which summarised and commented on the paper.

Ministers and Civil Servants Cannot Reform Whitehall On Their Own

Parliament needs to engage with the cultural and constitutional aspects of reform

Reform have recently published another fascinating paper as part of their Reimagining Whitehall work stream. Its title is Breaking Down the Barriers: Why Whitehall is so hard to reform.

The paper summarises interviews with twelve former Cabinet and Permanent Secretaries, six former Cabinet Ministers and nine other 'Great and Good'. It thus leaves itself open to the criticism that Reform should have also interviewed some less senior officials including those in offices outside London.

To be fair, however, Reform were in effect asking interviewees to admit why they had (individually and collectively) failed to lead change Whitehall. It is to their credit that they were not over defensive in their responses.

Taken together, they identified ten barriers to change which I have for convenience divided into three:

1. Ministerial and Permanent Secretary Lack of Interest

2. Cabinet Government

3. Incompetent Change Management

Ministerial and Permanent Secretary Lack of Interest

Reform's interviewees identified the following problems:

· Ministerial uninterest

· A bias for policy and ministerial handling skills over corporate and organisational capabilities in promotionHere are some [lightly edited] quotes:

"Permanent secretaries ask themselves: Do I take a phone call from the Chief Operating Officer. This reflects a wider civil service pathology that prizes ‘clever’ policy brains above operational expertise. As one former permanent secretary bluntly expressed it: “fast streamers don’t want to be COO John Manzoni, they want to be Cabinet Secretary Jeremy Heywood.”

"One politician used to describe implementation and policy as the blue collar and the white collar."

"Why have previous reform attempts failed? Answer: because the most powerful people in government - both politicians and civil servants - move their attention to the next most pressing policy issue of the day. And don't ... focus their attention on the machine that's delivering it. They don't lift their head - or perhaps bury their heads - into the machinery."

Comment: Senior Ministers’ strong preference for support from policy experts rather than those with operational skills is mainly driven by Ministers prioritising their own need to perform well in Parliament and the media. This important aspect of Whitehall’s culture (and our constitution) will need to change if there is to be meaningful reform. But any change in this area would need to be accepted by Parliamentarians.

Cabinet Government

Reform's interviewees identified the following problems:

· A poorly defined and weak executive centre

· Departmental fiefdomsIn other words, a Cabinet (of equals in) Government means that Permanent Secretaries feel primarily responsible to their Secretaries of State, who are seldom much interested in centrally driven initiatives such as Civil Service reform.

Here are some more quotes:

“...it’s a culture that’s manifested in a structure which prioritises departmental autonomy, essentially. That your loyalty, and I used to say this when I was in government, is primarily to your department. Secondly, but quite a long way second, to the government of the day.”

"The prizing of 'clever' policy brains above operational expertise, combined with Whitehall's siloed structure means that securing the buy-in and action of Permanent Secretaries is almost impossible."

It’s extraordinary how non-compliant permanent secretaries and DGs are. The centre is something you doff you cap [to] when in view, but as soon as they’re out of view, you just manage it…”

“Some permanent secretaries said we’re not going to roll it out in that department, it’s going to cost too much and we’re not doing it. And in effect could get away with it, because Francis Maude didn’t have authority over their secretaries of state.”

“It was really striking going from being the Permanent Secretary of an operational department like the Home Office to become Cabinet Secretary. At the Home Office, I'd sometimes find I'd pulled levers and commissioned work, even if I didn't know I had, just by casual remarks … so I had to learn to say 'OK everyone, just thinking out loud. No one's to do anything!' To being Cabinet Secretary, when I could barely find a lever that was connected to anything.”

Comment: It is likely, therefore, that Cabinet Government itself will need to be reformed as part of any Whitehall reform process. That would again represent a significant change to our constitution.

Incompetent Change Management

Reform's interviewees identified the remaining six problems:

· A lack of clarity about who is responsible for instigating change

· A leadership cadre with limited external experience and a status quo bias

· Insufficient investment in change management and poor communication of the tangible value for reform

· Limited attempts to build enthusiasts for reform throughout the civil service

· Limited exposure at all levels to alternative organisational models and ways for working

· The absence of a self-reforming, or stewardship, mentalityComment: None of the above problems are at all new. But strong and experienced change managers can overcome them. I was pleased, therefore, to see that at least one of Reform's interviewees had led successful change programmes. That person argued that ...

"Change management is a complex and resource-intensive process, and in general, the level of commitment required to succeed is rarely in place. In addition, the tangible value of that change to those expected to enact it is often poorly communicated, reducing buy-in and hindering success."

The general approach in Whitehall is more like a parody of tough change management. You look at change programmes in the corporate world, they don't enter them lightly because they know they are difficult things to manage. ... I worked for a private company they did a big change programme. I said to the CEO: 'How much of your time are you spending on this?' '50%'. 'For how long?' 'Six months'. Because you know, this was mission critical to the business ..."

"We had two directors that ... did nothing else but work for me and think about transformation, how do we get everyone to buy in, how do we communicate it, track progress, that sort of thing. That I think made a significant difference to implementation.

Analysis - Change Management

Different change management experts use different descriptors but they all talk about the need to identify something like “the six Cs”:- the key elements of any system, none of which can be permanently altered without simultaneously requiring or causing change in the others.:-

- Capacity:- i.e. resources, and in particular staff numbers

- Capability (or competence):- i.e. staff skills, training, experience and motivation

- Compensation - salaries, bonuses, appreciation

- Communications:- including not only communications whilst the change programme is being implemented, but also new ways of communicating once the changes have been implemented

- Culture:- new relationships, attitudes to innovation etc

- Constitution:- i.e. organisational structure, reporting lines etc.

Put another way, if you try to change one of the 'C's without changing the rest of the system then the system will over time, like this child’s flexible toy, snap back (revert) to its previous state.

This reversion can be seen throughout the history of civil service reform - witness the failure of so many ‘reform’ initiatives over many decades. It is particularly worrying that even the ostensibly successful efficiency programmes seem to have failed over the longer term. Professor Christopher Hood examined this subject with Ruth Dixon when they published 'A Government that Worked Better and Cost Less? - Evaluating Three Decades of Reform and Change in UK Central Government'. Their conclusion? Over a thirty year period of successive reforms, the UK exhibited a striking increase in running or administrative costs (in real terms) while levels of complaint and legal challenge also soared. (The counterfactual - what would have happened without the efficiency programs - might have been worse, of course, but their findings were hardly cause for celebration.)

Most Whitehall reformers do seem to recognise the interrelationship between the first four Cs, even if Ministers try to ignore them. You shouldn't, most obviously, try to cut staff numbers unless you improve the average capability of those that remain - and then you probably need to pay them more.

However - to pick up Reform's themes '1' and '2' above - Whitehall reformers have found it hard, verging on impossible, to address cultural and constitutional issues in the absence of engagement with Parliament itself.

Former Permanent Secretaries Jonathan Slater and Philip Rycroft, for instance, argue that Whitehall's culture should in future encourage senior officials to be significantly more accountable for the advice that they give to Ministers. But I have seen little evidence that Ministers would welcome this. And most MPs would much prefer to score political points by focussing on ministerial successes and failures rather than give credit to, or blame, senior officials.

It is also relevant that, although recent Prime Ministers have tried to become more Presidential and less 'first among equals', none of them have got anywhere near acknowledging the consequences for the constitution. The Whitehall machine has accordingly become increasingly confused and dysfunctional, as described by Reform's interviewees.

Where Next?

This Reform report, like so many before it, has shown that no Ministerial team and no Civil Service Leadership team is ever, on their own, likely to be able to lead a change programme in which all of the six 'C's are simultaneously changed in a way that creates a new stable configuration. It is in particular very difficult (and it would surely be wrong) to change Whitehall's culture and the country's (unwritten) constitution without involving Parliamentarians.

So how do we establish a change programme which involves Parliamentarians and yet is sufficiently politics-free to command wide respect? Maybe it will be impossible until we have recovered from recent political and economic earthquakes? In time, though, maybe we will need the modern day equivalent of Haldane or Fulton?

Martin Stanley

RPC Annual Report Makes Grim Reading

Here is a self-explanatory Substack Post that I published in September 2023:

The Regulatory Policy Committee published its annual report earlier today.

“There has been a concerning increase in the number of red-rated Impact Assessments that are ‘Not Fit For Purpose’, as well as an increase in Impact Assessments submitted late by departments (in some cases where the legislation was already before Parliament) …

… Another disappointing trend has been the failure of departments to complete post-implementation reviews of their regulations despite it being a statutory requirement.”

Call me ‘old fashioned’ etc. but …

What was going through the minds of the civil servants who decided that they did not need to write timely IAs that were fit for purpose, let alone comply with post-implementation review legislation?

It looks as though they were in clear breach of the Civil Service Code which requires them to:

always act in a way that is professional and that deserves and retains the confidence of all those with whom they have dealings; and

comply with the law.

Does it matter? The Code also says that:

[Compliance with this Code ensures] the achievement of the highest possible standards in all that the Civil Service does. This in turn helps the Civil Service to gain and retain the respect of ministers, Parliament, the public and its customers.

Did officials care? Did they object? What did their Permanent Secretary say when the failures were drawn to their attention?

MoD Equipment Plan

More evidence of the mounting problems across the whole of Whitehall was provided in a report that the MoD Equipment Plan was "unaffordable, with the MoD estimating that forecast costs exceed the available budget by £19.6 billion (6%)".

Permanent Secretaries: Their Appointment and Removal

The above-titled House of Lords report gave its subject a pretty clean (over-clean?) bill of health. They seem not to have been concerned that Heads of Departments' average years as Permanent Secretary fell from 8.5 in 2019 to 4.2 in 2023. (Para 109)

Here are some extracts:

Since our last report on the civil service in 2012, the relationship between

ministers and civil servants has become more exposed and controversial. Recent

departures of several permanent secretaries and civil servants of equivalent

seniority have also raised questions as to the degree of ministerial involvement

in the departure of senior officials as well as the appointment process, and

whether there exists a desire to appoint politically sympathetic candidates to

these positions.

While ministers are accountable for all aspects of their departments’ work and

have a legitimate interest in ensuring the right people are appointed to key posts

and that those who are appointed perform to the highest standards, this has to

be balanced against maintaining the constitutional principles under which the

civil service operates: integrity, honesty, objectivity and impartiality....

The current formal level of ministerial involvement strikes the correct balance.

It allows ministers input into the job description, the person specification and

the composition of the panel while preventing them from engineering the

process in favour of a preferred candidate. It preserves the concept of merit.

However, ministers are not always sufficiently aware of the extent of their

influence over appointments or the limits on it. They require further briefing by

their departments to avoid tension during the recruitment process and reinforce

ministerial ownership of the process....

For a permanent secretary, fostering a positive relationship with the secretary

of state is an element of effective performance and it is rare that a breakdown

in this relationship will occur. However, forming a positive relationship is a

two‑way process and incoming ministers must allow permanent secretaries

time to establish a productive relationship. If an irrecoverable relationship

breakdown might have occurred, the Head of the Civil Service has a vital role

to play in ensuring due process is followed.

It is particularly important that removal of a permanent secretary on the

grounds of a poor working relationship does not become cover for arbitrary

removal of permanent secretaries on personal, political or ideological grounds,

which should not occur under any circumstances....

We do not consider the small number of recent high-profile removals of senior

civil servants on what appeared to be political or ideological grounds to amount

to a trend. Nonetheless, some recent departures and appointments have been

conducted in the public eye and might be seen to reflect a desire on the part

of ministers to personalise appointments and assert their authority. This risks

civil service turnover coinciding with ministerial churn, creating a perception

of politicisation and damaging institutional knowledge....

Fixed five-year tenure

104. Fixed five-year tenure was introduced for standard permanent secretary

contracts in 2014. The tenure applies to the role rather than the individual—

in the words of the Cabinet Office: “an individual’s contractual rights and

underlying permanent employment status are unaffected by their tenure

period in a particular role at this level.” While there is no automatic

presumption in favour of renewal, renewals may be granted at the discretion

of the Prime Minister where a permanent secretary’s performance is strong.

105. Lord Sedwill explained the process as follows: as the five-year point

approached the Head of the Civil Service would talk to the permanent

secretary during their annual appraisal to ascertain whether they intended

to apply for an extension. The Head of the Civil Service would then consult

the secretary of state and the Prime Minister before making any formal

recommendation. The Cabinet Office explained that, if an appointment

was not renewed, the permanent secretary was expected to depart their post

when the tenure period ended. If an appropriate alternative post could not

be identified compensation might be offered.

Civil Unrest

A Reform think tank report, written by Amy Gandon and with the above arresting title, was published in October 2023, reporting the thoughts, concerns and hopes of a wide cross section of civil servants. You can read the report here - and this is its (admirably short) Executive Summary:

The civil service and its effectiveness have long been the subject of debate, but never more so than over the past few years. What has too often been missing from those discussions is the voice of civil servants themselves.

This report seeks to redress that balance. Through the anonymous testimony of 50 civil servants, it provides an ‘insider’s look’ into government through Brexit, the COVID-19 pandemic and a period of broader political instability. In so doing, it challenges the perception of civil servants as an undifferentiated or obstructive ‘blob’. The officials interviewed were not only aware of the Service’s flaws but deeply frustrated by them and eager for change.

The hope is that this work will pave the way for a more constructive, even co-productive, approach to reforming the civil service in future.

The following themes emerged most strongly and commonly across the fifty interviews:

- An ambition to serve the public and deliver impact but frustration with how difficult this was in practice, with much of their time taken up by briefings and ‘busy work’ over analysis and policymaking (see Chapter 2).

- A feeling that government had become more reactive and short-termist in recent years, and less anchored in a stable, long-term vision for the future. Many participants felt a more politically volatile environment meant more effort being spent on announcements and ‘good news stories’ than on long-term solutions and implementation (see Chapter 3).

- A noticeable shift in the relationship between ministers and civil servants, with mutual mistrust making it difficult to give honest advice and make decisions efficiently. Some felt ministers were right to suspect officials of political bias, while others felt their duty to challenge had been misinterpreted as resistance (see Chapter 4).

- Lack of admiration for civil service leadership, which was felt to be an increasingly difficult role in the face of greater public profile and strained relationships with politicians. Very few participants aspired to the senior ranks, unwilling to deal with the pressures and ‘small p’ politics involved (see Chapter 5).

- Further decline in the civil service’s ability to manage and retain talent over the past few years, with significant demands – especially from Brexit and the pandemic – leading to inexperienced staff being recruited and promoted. With higher workloads and a squeeze on pay, participants felt the civil service was now a less attractive place to work on top of long-standing issues around promoting expertise and reducing churn (see Chapter 6).

But while their testimony paints a difficult picture of life in the civil service, participants invariably found their work stimulating and important. Many shared examples of inspirational leadership from civil servants and ministers alike. Ultimately, they had plenty of ideas to inform a positive agenda for change, summarised in our eight key principles for reform (see Conclusion). Politicians and senior officials would be wise to consider these if future reforms are to carry the support of the half a million civil servants they affect.

Checks and Balances?

Writing in November 2023 about Covid and Boris Johnson, Andrew Rawnsley bemoaned the ineffectiveness of "the structures that are supposed to be in place to protect the country from such a terrible prime minister. The UK was unprepared to handle a rogue pathogen or a rogue leader and had the misfortune to be afflicted with both at the same time. He continued ...

One of the checks and balances on a prime minister going totally off the rails is supposed to be the civil service. “Speaking truth to power” has traditionally been part of the remit, and the voice needed to be especially insistent when the power was being wielded so atrociously. This didn’t happen and it is not the only dismal failure by the senior echelons of the mandarinate. Helen MacNamara, deputy cabinet secretary during the pandemic, confessed to the inquiry that she would “find it hard to pick one day” when Covid rules were “followed properly” at Number 10. And she knows of what she speaks because it was she who carted in a karaoke machine for one of the infamous lockdown-busting parties. Her responsibilities at the time – reader, I weep – included government propriety and ethics.

The two most important officials in the life of a prime minister are his principal private secretary and the cabinet secretary. If Martin Reynolds, the private secretary, had been performing his role appropriately he would have insisted to the prime minister that everyone in Number 10 had to be extremely careful to ensure they were strictly adhering to the Covid laws and regulations that they were imposing on the nation to contain a deadly disease. Rather than do everything he could to prevent the scandal that became known as Partygate, it was “Party Marty” who sent out the invitations to the notorious “bring-your-own booze” gathering.

The cabinet secretary cuts an even more abject figure. Material published by the inquiry records Britain’s most senior civil servant telling colleagues that he is “at the end of my tether” with a prime minister who makes an effective response to the crisis “impossible” by changing “strategic direction every day”. The cabinet secretary is expected to be the wise man of government and a figure with sufficient gravitas to cajole a bad PM to correct his ways. Mr Case comes over as a grizzling child so devoid of authority that he bleats: “Am not sure I can cope with today. Might just go home.”

The Maude Report

Lord (Francis) Maude's report The Independent Review of Governance and Accountability in the Civil Service was published in late 2023. It was particularly interesting because Lord Maude argued that the report should not be understood as an attempt to fix the problems of the civil service, but instead contained recommendations for the preconditions needed for effective and long lasting change. He outlined a number of critiques of the civil service – its closed culture, reliance on generalists, churn and emphasis on policy over implementation, among others – his recommendations generally did not focus on solving these specific problems. Instead, Maude hoped that his report would provide both diagnosis and solutions to why these problems, well known and longstanding as they are, had not been effectively dealt with in government.

Max Emmett's insightful review of the report is here. He concluded that:

The report is a significant piece of work that both government and opposition would do well to read closely. It contains sensible recommendations about departmental boards, collective decision-making and ministerial and Special Adviser training and accountability. The principal recommendations on reform of the centre come out of an entirely legitimate and understandable frustration with past failures of the civil service reform agenda.

However, the proposed reforms attempt to provide institutional solutions for what are essentially political problems. It is unclear whether they could overcome the inertia of the civil service when it comes to reforms without significant political weight behind them. When in office, Maude provided the necessary leadership to make progress. The job is certainly far from finished, but this is a task that needs to be taken up by the next generation of ministers.

The key lesson the next government should learn from the report is the value of having an experienced minister with a long-term interest in reform continually pushing to create a government that can best serve the public good.

My own summary of, and initial comments on, the report may be found in this 2023 blog.

Developments in 2024 may be found here.