The phrase civil service reform is used in two quite distinct ways. It is often used by politicians and senior officials as short-hand for efforts to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the c.400,000 civil servants who work around the UK – paying benefits, protecting our borders, collecting taxes and so on. But this is a misuse of the word ‘reform’, which should surely suggest more fundamental change in the way in which the civil service behaves and operates. And the behaviour of the UK civil service is in turn deeply bound up in its structure, its culture, and the incentives of its leaders in ‘Whitehall’.

(Note that almost all of the debate about true civil service reform - and indeed almost all media comment on the civil service - concerns the relatively small proportion of the civil service - no more than few thousand - who work closely with Ministers. Most civil servants are busily engaged in on executive tasks all around the UK and no-one questions the legality, impartiality or nature of their activities. Even in Whitehall, the supposedly seismic events that hit the headlines have little or no relevance even to most senior officials' daily activities.)

The most recent report that dealt with fundamental civil service reform was published as long ago as 1918. The Haldane Report was unambiguously aimed at improving the effectiveness of government policy-making, and led to fundamental changes affecting policy makers and other senior officials. Now, nearly 100 years on, the quality of policy making, and support for Ministers more generally, is generally reckoned to be patchy. Too much of the best civil service policy-making talent is nowadays devoted to maintaining the governing party in power rather than in formulating and delivering policy. Ministers have responded in piecemeal fashion (by strengthening the centre of government, by introducing and then strengthening departmental boards, etc.) but there has been no serious review of the fundamental relationship between Parliament, Ministers and civil servants. This part of this website discusses these question, and has three levels, so you can dig as deep – or not – as you wish.

- This introduction summarises the key issues and arguments.

- There are eight pages that look at each of the issues and arguments in greater detail.

- And then there is a very detailed history from the 1850s right up to the present date.

To begin at the beginning …

The Northcote-Trevelyan Report - 1854

In the absence of fundamental reform, the UK civil service retains many of the characteristics of the service that was created as a result of the 1854 Northcote Trevelyan Report on the Organisation of the Permanent Civil Service. Interestingly, the need for reform then was driven by circumstances which have immediate resonance today: 'The great and increasing accumulation of public business, and the consequent pressure on the Government'. The result was a civil service mainly appointed on merit through open competition, rather than patronage, with four core values: Integrity, Honesty, Objectivity and Impartiality - including political impartiality.

Why 'mainly'? Northcote and Trevelyan were mainly concerned about the efficiency and effectiveness of those who were employed in what we would now call delivery functions. These officials were to be recruited and promoted on merit. But the two authors were more relaxed about those close to Ministers being appointed otherwise than through examination etc:-

It is of course essential ... that men of the highest abilities should be selected for the highest posts; and it cannot be denied that ... it will occasionally be found necessary to fill [such posts] with persons who have distinguished themselves elsewhere than in the Civil Service ... there will be some cases in which examination will not be applicable. It would be absurd to impose this test upon persons selected to fill the appointments which have previously been spoken of ... on account of their acknowledged eminence in one of the liberal professions, or in some other walk of life.

Charles Trevelyan's particular hobby horse was that low-grade tasks, which he called 'mechanical' should not be carried out by 'intellectuals'. This eventually led to the separation of recruitment from universities from the recruitment of clerks, thus facilitating the dangerous divorce of policy-making from policy implementation. One practical result of the post-Northcote-Trevelyan discussions and decisions was thus a civil service that placed little value on management and leadership.

Exactly the same problem bedevilled the Fulton Report and the Next Steps Programme. Further discussion of these issues may be found in this and subsequent detailed notes.

The Haldane Report - 1918

The next major set of reforms came about as a result of the 1918 Haldane Report, published at the end of the First World War. Haldane recommended the development of deeper partnerships between Ministers and officials so as to meet the more complicated requirements of busier government as substantial executive ministries emerged from the first world war. The Report's impact came through two closely-linked ideas:

- Government required investigation and thought in all departments to do its job well: "continuous acquisition of knowledge and the prosecution of research" were needed "to furnish a proper basis for policy". Gone were the days when government Bills and decisions could rely on the expertise of Ministers, MPs and outside opinion. Ministers could not provide an investigative and thoughtful government on their own. Neither could civil servants, but a partnership between both could.

- The partnership must be extended, however, from the cluster of officials round a Minister, typical of 19th century government, to embrace whole departments as the repositories of relevant knowledge and opinion. Haldane did not spell out how such investigation and thought were to be developed, except to recommend they should be based on a split of functions between government departments which essentially has continued to this day.

The relationship between civil servants and Ministers thus became one of mutual interdependence, with Ministers providing authority and officials providing expertise.

Again, however, the post-Haldane culture has disadvantages which have arguably become more serious in recent years Officials' accountability to Ministers, and not to Parliament, means that there is very little effective scrutiny of the practicability of Minister's policies. Ministers can and do announce impossible targets and under-resourced programs safe in the knowledge that failure, maybe years later, is very unlikely to be career threatening. Experts will of course criticise the targets etc. when they are announced but ... who needs experts when the government benches and government-supporting media sing their praises? It is perhaps particularly distressing that the civil service - knowing full well that the programs are flawed - will nevertheless help Minister mount a strong defence of them both in Parliament and the media.

Management and Efficiency Reports

All the key reports and initiatives since 1918 have focused on management and efficiency. Even the far-reaching 1968 Fulton Report looked only at the structure, recruitment, management and training of the civil service. Indeed, its authors complained that they were not allowed to look more widely at questions such as the relationship between Ministers and officials, and the number and size of departments, and their relationships with each other and the Cabinet Office.

The post-1979 Thatcher government then focused on improving the efficiency of the big, high-spending departments and achieved notable success, including sharpened financial management and the establishment of separately managed 'Next Steps' Executive Agencies. Mrs Thatcher's and subsequent governments also delegated considerable power to various regulatory bodies, including the Bank of England, the utility regulators and bodies such as Ofcom and Ofsted.. These developments are extensively discussed in the Understanding Regulation website, whilst the political and social implications are the subject of much academic analysis - not least Michael Moran's The British Regulatory State.

Subsequent reform programs have also been essentially managerial, and have addressed subjects such as leadership, performance management, the role of the Senior Civil Service and improved delivery.

Cabinet Office officials have from time to time tried to focus Ministers' and colleagues' minds on the need to consider what might be regarded as constitutional issues (see this 1998 Memorandum on Accountability and Incentives, for instance) but such efforts meet with indifference or worse. My own failed attempt to inject some life into the same reform programme is here. Patrick Diamond noted in 2021 that:

What was more significant was the ‘identity crisis’ that afflicted the civil service, prompted by the failure to clarify its constitutional role against the backdrop of growing concerns about the ‘elective dictatorship’, particularly under Thatcher and Blair. ... the civil service was reluctant to engage in public debate about its future. The preferred strategy was the time-honoured approach of ‘muddling through’, striving to protect their relative privilege and status in an era of unprecedented turbulence.

The detrimental impact of the politicisation of the government machinery on the quality of statecraft is palpable. British government is more exposed to blunders and fiascos. Delivery failures have ranged from the politically catastrophic poll tax to the negotiation of botched public procurement contracts that cost the taxpayer billions. Writing in the Financial Times in April 2012, the political scientist, Anthony King, observed that policy making increasingly resembled ‘a nineteenth century cavalry charge’ with insufficient deliberation. After Brexit, these failures may become even more palpable.

There are fundamental issues still to be resolved: what are the respective roles of ministers and officials? How can civil servants be protected from unwarranted political interference? What role should ministers play in appointing officials? How can political advisers be effectively scrutinised? Should the appointment of special advisers be independently regulated?

After forty years of reform, the system of government in which ministers and officials worked to fashion effective policies has morphed into a ‘them and us’ model where politicians and civil servants are at odds, believed to have conflicting interests.

Kevin Theakston added that:

... the constant waves of reform also had a destabilising effect on staff and their morale. Furthermore, there were real problems concerning the arrangements for ensuring accountability in the much more fragmented world of executive agencies, delegated management and a more ‘Balkanised’ civil service. In politically charged situations there was shown to be plenty of scope for blurred accountability and buck passing between ministers and agency chief executives and civil service managers when things went wrong. The government and the Whitehall top brass themselves were arguably too blasé or even disingenuous about the constitutional implications of the Next Steps and other managerial changes for parliamentary and public accountability, and the meaning of ministerial responsibility.

The civil service has, over the years, undoubtedly become better managed, more efficient and less stuffy in its higher reaches. It attracts some very bright, energetic and personable young people and in general seems to provide as good a service than similarly large organisations in the private sector. But the more high profile change programmes (1999 - 'Modernising Government'; 2004 - 'Civil Service Reform: Delivery & Values', 2009 - 'Gershon' and 'Lyons' - 'Putting the Front Line First') have achieved much less than they might have done, which is why the initiatives come along so frequently.

One perhaps inevitable weakness is that it has proved hard to set public, measurable objectives for senior officials in general, and for Permanent Secretaries in particular. Follow this link to read a short discussion of this issue.

The latest Civil Service Reform Programme. for instance, was driven by the need to cut the number of civil servants as part of the post-2010 austerity drive. This made the civil service machine look more efficient, but there was a trade off in terms of poorer customer service, less well-informed advice to Ministers, and so on. There are some signs that this has become a problem - see Civil Service Reform Detailed Note 7 et seq.

A more detailed note on managerial and efficiency reforms is here, and a Colin Talbot's very readable brief history of performance measurement is here. I also recommend this separate commentary which describes Civil Service Reform Syndrome and explains why management/efficiency reform programs are too often set up to fail.

But - returning to the subject of 'proper' civil service reform - critics assert that the traditional Whitehall/Westminster Model of government is unsuitable for the modern world. Yes, Minister’s author Sir Anthony Jay’s summarised the argument rather nicely on the Today Program on 6 April 2012: ‘We have a really rather silly system. If you look at any big corporation you will find that the people at the top are concerned about the product and they are concerned about the market. They are concerned about what they produce and sell, and they are concerned about the people that they are selling it to. But in politics we divide it up. We have a lot of people who are only concerned about what they are doing and what they are making and another lot who are really concerned about very little except marketing and getting public approval.’

Is it indeed possible to build a more detailed case for government/civil service reform. Those that seek to do so use three main arguments.

First, they point to the substantial changes that have taken place in British government and society since 1918 – globalisation, joining the European Union, devolution, the growth of the regulatory state, the decline of deference, the greatly increased power of the media, 24/7 social media, and so on. Today’s politicians are relatively powerless compared with their predecessors 100 years ago. Further detail is here.

Second, critics point to a succession of government ‘blunders in recent years, including the Poll Tax, the Child Support Agency, our joining and leaving the Exchange Rate Mechanism, and a wide and very expensive range of disastrous IT projects. Further detail is at here.

Note that these first two arguments suggest the need to reexamine the relationship between Parliament, Ministers and officials.

Note that these first two arguments suggest the need to reexamine the relationship between Parliament, Ministers and officials.

The third argument points to weaknesses in the Civil Service itself. Senior Civil Servants too often appear to be in a world of their own, out of touch, poor managers, defensive, occasionally incompetent, and far too keen to act as Ministers’ courtiers, rather than speaking truth to power. The full charge sheet is here.

But …

It is less clear what sort of change would improve the performance of the government machine. Prime Ministers have tried greater centralisation of power, target setting, more devolution, and giving more power to departmental boards and Special Advisers. But none of these seem to have made much difference. Further detail is here.

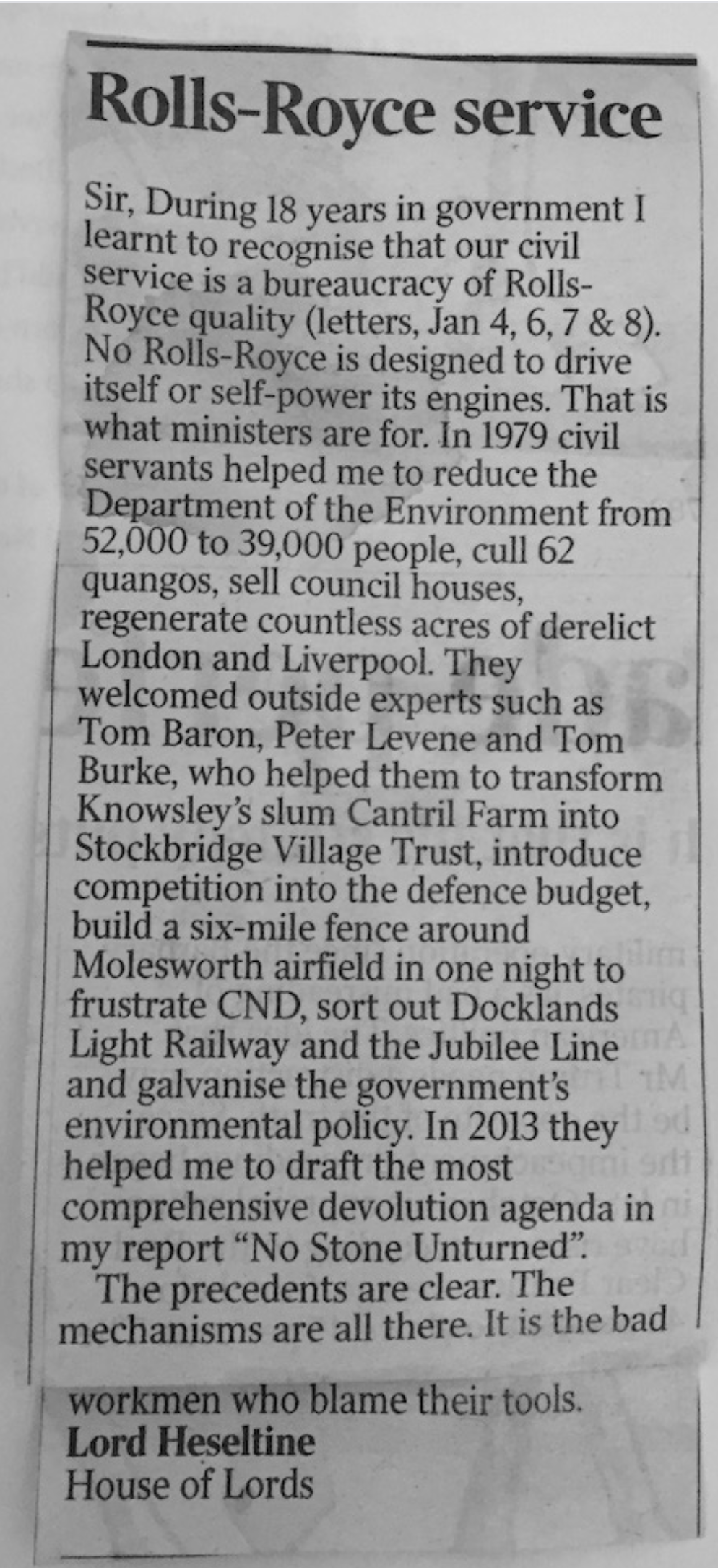

It is nevertheless possible to imagine some ways in which real reform might be brought about. Part of the answer must lie in re-thinking the relationship between Parliament, Ministers and officials. The civil service is, after all, an instrument of government, and - like any tool - is only as good as its user. Some Ministers find it relatively easy to get the support they need - see letter opposite - but it is clear than many do not.

Some would start by 'reforming' the Treasury. Robert Shrimsley (criticising the Treasury's opposition to regional devolution) described it as '[squatting] like a complacent toad over all policy. Its groupthink, innate fiscal orthodoxy and and resistance [to the policy proposals] have made it a block to progress. ... Whitehall will never be rewired until the Treasury is reformed. '

Politicisation of the upper reaches of the Civil Service might also make a difference. Or Ministers might no longer be held personally responsible for all the key decisions taken by their departments, but instead responsible mainly for establishing the Government’s strategy, leaving officials responsible and accountable for implementation. There is a more detailed discussion here, including an explanation of what stops these reforms from happening – with a suggestion that the main culprit may not be the Civil Service, but politicians themselves.

The Unadmitted Death of the Westminster Model?

David Richards and Martin Smith published a wide-ranging article in 2015/16 (The Westminster Model and the "Indivisibility of the Political and Administrative Elite") which nicely summarised 'the rhetorical gap between claims by the political class that the Whitehall model remains unchanged and the reality that suggests something quite different' - and this was before Brexit, Theresa May, Boris Johnson and Liz Truss! The Thatcherite New Public Management, they argued, had turned officials into rational actors whose goals were potentially in conflict with those of their political masters. This had spelt the beginning of the end of the Haldane Ministerial/official symbiosis which had been replaced by a more conflictual, binary relationship.

Their final paragraph was particularly perceptive, or apt, given the numerous public policy failures that became all too obvious over the following years.

There is also a real danger of a loss of expertise and of objective policy making. One of the skills of the traditional approach was to be small 'p' political and to understand the consequences of particular courses of action. Problems have arisen, particularly in the British system with its absence of checks and balances, when advice in these areas has not been taken on board, ignored or more crucially not been made available. We would argue this has occurred the cause the deliberative space to provide critical input has contracted. The drift away from the Westminster model, in terms of the eschewing of symbiotic minister- civil servant relationship to be replaced by a principal- agent approach has compounded the problem.

A Summary of All the Criticisms

There is a pretty good summary of the criticisms of the Civil Service, their history, and the relationship between them, in Annex 3 of the 2023 report by Lord (Francis) Maude.

Annex 4 of the same report discusses how the Civil Service might be made more 'porous' through improved interchange with other sectors, and is well worth reading. It concludes in this way: 'This Annex is not intended to set out a programme of reform. It is simply intended to illustrate, for one of the most commonly noted critiques of the Civil Service, how complex and challenging it will be to achieve real change. Persisting with the current arrangements for governance and accountability and expecting different results is unlikely to succeed.'

Official Histories

If you need more detail than is in these web pages, I strongly recommend:

- Rodney Lowe - The Official History of the British Civil Service - Reforming the Civil Service, Volume 1 - The Fulton Years, 1966-81

- Rodney Lowe and Hugh Pemberton - ditto, Volume II, The Thatcher and Major Revolutions, 1982-1997

And the House of Commons Library published an excellent history of Civil Service Reform through to 2010.

Further Reading

Peter Thomas is building a website ( civilservicereformuk.com ) focussed on recent and current developments in civil service reform in the UK.