The demands of the 1939-45 Second World War required substantial change in the civil service, and within Government more generally, including the employment of large numbers of strong characters and experts who would otherwise have remained outside government. This trend was put into reverse after the war but the experience appears to have informed those who in due course wrote the 1968 Fulton Report which looked at the structure, recruitment, management and training of the civil service. (It is interesting to note that its authors complained that they were not allowed to look more widely at questions such as the number and size of departments, and their relationships with each other and with the Cabinet Office.)

The report identified the following weaknesses in the civil service:

- It was too much based on the philosophy of the 'generalist' or 'all-rounder'.

- Scientists, engineers and other specialists were not being given the responsibilities, opportunities and authority they should have.

- There were too few skilled managers.

- There was not enough contact between the service and the community it serves.

- There was inadequate personnel management and career planning.

The report was taken seriously and led to significant change within the civil service, though not to the fundamental - and arguably elitist - Westminster/Haldane Model of government.

But pay restraint together with a wide range of other concerns led to the first ever national civil service strikes in 1973, which in turn led to the Wider Issues Review whose report Civil Servants and Change was published in 1975.

- More detailed information about the report is here.

- The main text of the report is here.

- The Joint Statement by the National Whitley Council, List of Contents and Annexes are here.

The post-1979 Thatcher government then sought to make progress on two fronts, and the ‘New Labour’ Government, elected in 1997, continued to make significant managerial and efficiency improvements.

New Public Management ...

... is a somewhat vague phrase which essentially summarises efforts to introduce competition between different public agencies, and between public agencies and private firms, and so incentivises innovation, efficiency and good customer service. New public management accordingly treats beneficiaries of public services as customers, and citizens as shareholders. It has been most obviously applied in the health and education sectors, and through contracting out support services. These reforms – which were continued by all successor governments - are not dealt with in any detail in this website, although it is worth noting that many believe that insufficient effort was put into getting the civil service ready to manage this more competitive environment. This led to significant problems with many of the programs, and to excessive costs being incurred on contracted out services (especially IT) and on consultants who were brought in to help introduce competition.

Patrick Diamond's view is that ...

NPM was scarcely a coherent doctrine. It combined an emphasis on private sector management expertise with theoretical propositions drawn from public choice economics. Bureaucrats were held to be fundamentally self interested agents, drawing on ideas advanced by the American economist, William Niskanen, in the 1970s. The aim was to replace the hierarchical public administration of the postwar era with accountable public management where managers were ‘free to manage’ flexible and non-bureaucratic organisations. NPM was accompanied by cuts in government budgets, reflecting the emphasis of Treasury-imposed efficiency. UK civil service numbers fell sharply from 735,000 to 430,000 by the 1990s.

The political impetus for NPM across western countries was powerful. In Britain, the backdrop was perceived economic decline, a belief that the state was inefficient and must be radically overhauled. The civil service was implicated in the overloaded state and the apparent ‘ungovernability’ of Britain. As befitted the ideas of Niskanen, politicians of right and left became acutely suspicious of bureaucrats. It was believed the government machinery was inclined to crush radical ideas that would shake Britain out of its postwar lethargy. The New Right devised a strident analysis of state failure which influenced the Thatcher administration, even if reform ideas were not always translated into practice.

... the patchy implementation of NPM reflected the doctrine’s inherent flaws. There was a fundamental difference between the public sector and the private sector which NPM advocates refused to acknowledge. Public goods cannot be allocated according to the profit motive. Politics inevitably intrudes on the process of public management. Moreover, the relentless focus on financial efficiency undermined quality and effectiveness. Professor Christopher Hood and his co-author Ruth Dixon calculate that NPM in the 1980s and 1990s ‘cost a bit more and worked a bit worse’. The aim was to ‘empower’ the public service consumer. Yet NPM enforced the ‘fetish for process’, heralding the relentless rise of the audit culture. NPM was oblivious to the complexity of governance in advanced economies.

Efficiency Initiatives: Separately, the Thatcher Government and its successors have focussed on improving the efficiency of the big, high-spending departments. Here, the existing civil service has been on more comfortable ground. It has considerable experience of delivering services on a large scale and in managing large numbers of staff across the UK. Senior officials accordingly reckon that they can steadily improve efficiency and customer service as long as politicians refrain from changing the rules – or at least don’t do so too often or too dramatically. There was considerable early success, including sharpened financial management and the establishment of separately managed 'Next Steps' Executive Agencies. Subsequent reform programs have also been essentially managerial, and have addressed subjects such as leadership, performance management, the role of the Senior Civil Service and improved delivery.

There have also been huge investments in information technologies which appear to have made the civil service much more efficient, and have eliminated huge numbers of lower paid jobs in areas such as taxation and licensing. It should be noted, however, that many of the apparent productivity gains result from getting taxpayers, licensees, benefits claimants etc. to do 'shadow work' - that is work previously done by civil servants. This was nicely described in a 2023 article by Rana Foroohar.

Lord Bancroft's Lecture, Whitehall and Management: A Retrospect, provides a thought-provoking and entertaining review of management reforms through to 1984.

Sir Geoffrey Holland praises the creation of Agencies, but offers a pretty scathing review of privatisation, market testing and contracting out, at pp 45-46 of his 1995 lecture "Alas! Sir Humphrey, I Knew Him Well".

Colin Talbot wrote a brief history of performance management in 2017.

The following is a list of the key managerial reform documents through to 2012.

- The Financial Management Initiative (1986) sought improvements in the allocation, management and control of resources.

- Improving Management in Government; The Next Steps (1988) led to much of the executive work of Government being devolved to Executive Agencies.

- Prime Minister John Major's Citizen's Charter, launched in 1991, was a well-meaning attempt to make public bodies more responsive to the needs of their customers. But it wasn't aimed mainly at the civil service, and was met with a good deal of coolness by senior officials. It may be that (rather like subsequent PM David Cameron's Big Society) it had not been sufficiently well-designed or well-planned in advance. Sadly, therefore, it ran out of steam pretty quickly.

- It is worth noting that the Inland Revenue and Customs and Excise had jointly published a Taxpayers' Charter in 1986. A more focussed version was published in the 1990s. Click here to see the 1995 version. The two departments eventually merged to form HM Revenue and Customs who have, to their credit, maintained the charter through to the present day.

- The 1993 Oughton Report led to some useful improvements in the management of (what became) the Senior Civil Service, although some of his recommendations were unwelcome and therefore ignored.

- The 1994 'Continuity and Change' consultative White Paper and the 1995 'Taking Forward Continuity and Change' decision document led to:

- the delegation of further management flexibility and freedoms, including delegation of pay and grading decisions, to individual departments

- the establishment of the Senior Civil Service, and greater use of recruitment from outside the civil service ('open recruiting') and more flexible remuneration arrangements at senior levels.

- the promulgation of the Civil Service Code, and

- an enhanced role for the Civil Service Commissioners in recruitment and selection on merit.

- Prime Minister Tony Blair and Chancellor Gordon Brown introduced Public Service Agreements in 1998, and ...

- ... the PM established the Prime Minister's Delivery Unit in 2001.

- 'Modernising Government' (1999) had a strong civil service reform element. Indeed, the then Head of the Civil Service told the Prime Minister that he and his Management Board 'pledged themselves personally to drive forward a new agenda' including

- Stronger leadership

- Better business planning

- Sharper performance management

- A Service more open to people and ideas, and which brings on talent, and

- A better deal for staff.

- 'Civil Service Reform: Delivery and Values' was published in 2004. It was an insubstantial document promising greater emphasis on 'delivery' without any clear explanation of how this was to be achieved. The Gershon and Lyons reports ('Putting the Front Line First'), published around the same time, had a much harder edge, promising significant reductions in civil service numbers - especially those employed in London and the South-East. The 'Lyons' link in the previous sentence will take you to the report's executive summary. The full report is here.

- 'Putting the Frontline First', published in 2009, contained little more than a series of cost-cutting measures.

- The austerity-driven Civil Service Reform Plan was published in 2012.

There is much more detail in these web pages. In particular, Detailed Notes 7 et seq look at the 2012 Reform Plan and the consequences of sharp reductions in staff numbers for the quality of customer service and the quality of advice for Ministers. And Note 16 summarises the introduction of a new vision statement with the promise of the development of a brilliant Civil Service with this new colourful branding:

Detailed Note 17 includes an interesting (and scathing) 2017 IfG review of departmental priorities and Permanent Secretary objectives.

11 Functions ('the Functions Initiative') and 25 Professions were introduced in the 2010s. There is further information about them in a 2017 NAO report and in a 2020 PAC report on Specialist skills in the civil service.

There is a nice tongue-in-cheek imagination of officials' response to efficiency initiatives here.

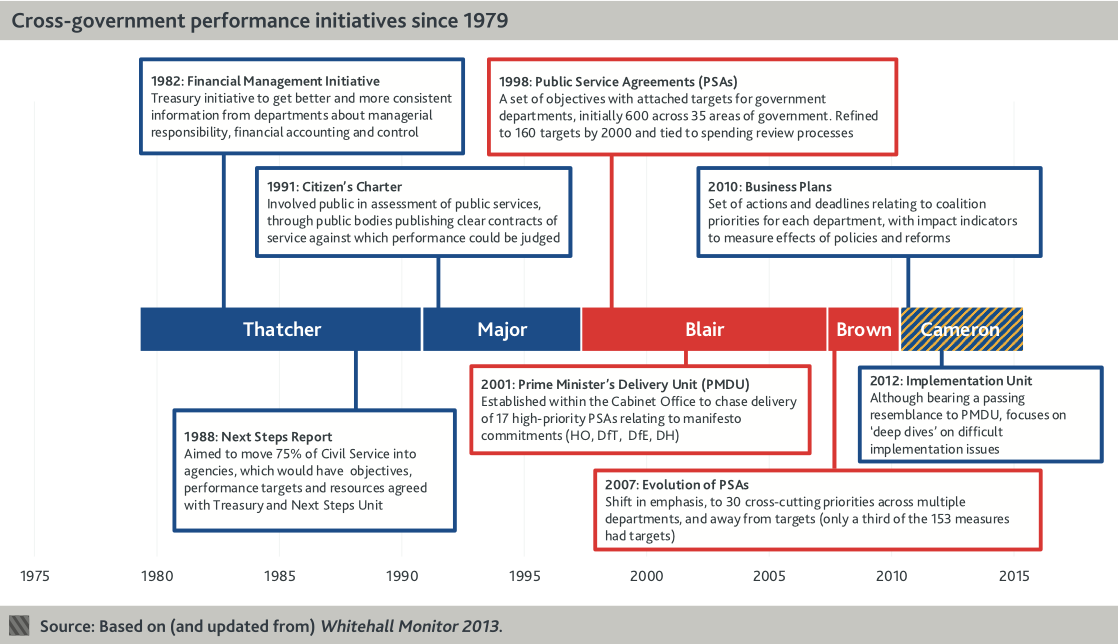

Here is a handy IfG summary of key performance initiatives:

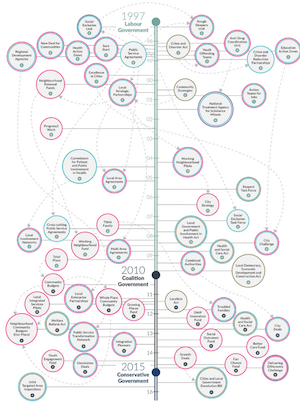

And the IfG in 2018 published a fascinating summary of attempts to join up public services. Their interactive timeline

shows the key national attempts to join up public services at a local level from 1997 to 2015. (Click on the image opposite to see a larger screen-shot. You might like to access the IFG website to access interactive detail, clicking on the circles to find out more about the individual initiatives, and related policies.)

And the IfG in 2018 published a fascinating summary of attempts to join up public services. Their interactive timeline

shows the key national attempts to join up public services at a local level from 1997 to 2015. (Click on the image opposite to see a larger screen-shot. You might like to access the IFG website to access interactive detail, clicking on the circles to find out more about the individual initiatives, and related policies.)

The Chief Executive of the Civil Service proudly unveiled Success Profiles a little later in 2018 - a new approach to recruitment within and from outside the civil service. It was very worthy but arguably over-complex, reducing (or rather expanding) common sense into endless charts and detail. Here is one: (Further detail is here.)

I recommend this discussion of the capability of the civil service as of late 2017.

2020 saw the publication of Talent Management Guidance. This again strikes me as over-complicated and far too detailed. I cannot remember anything like it being published in earlier decades when the civil service was arguably much better managed in many ways, though its senior ranks were certainly less diverse.

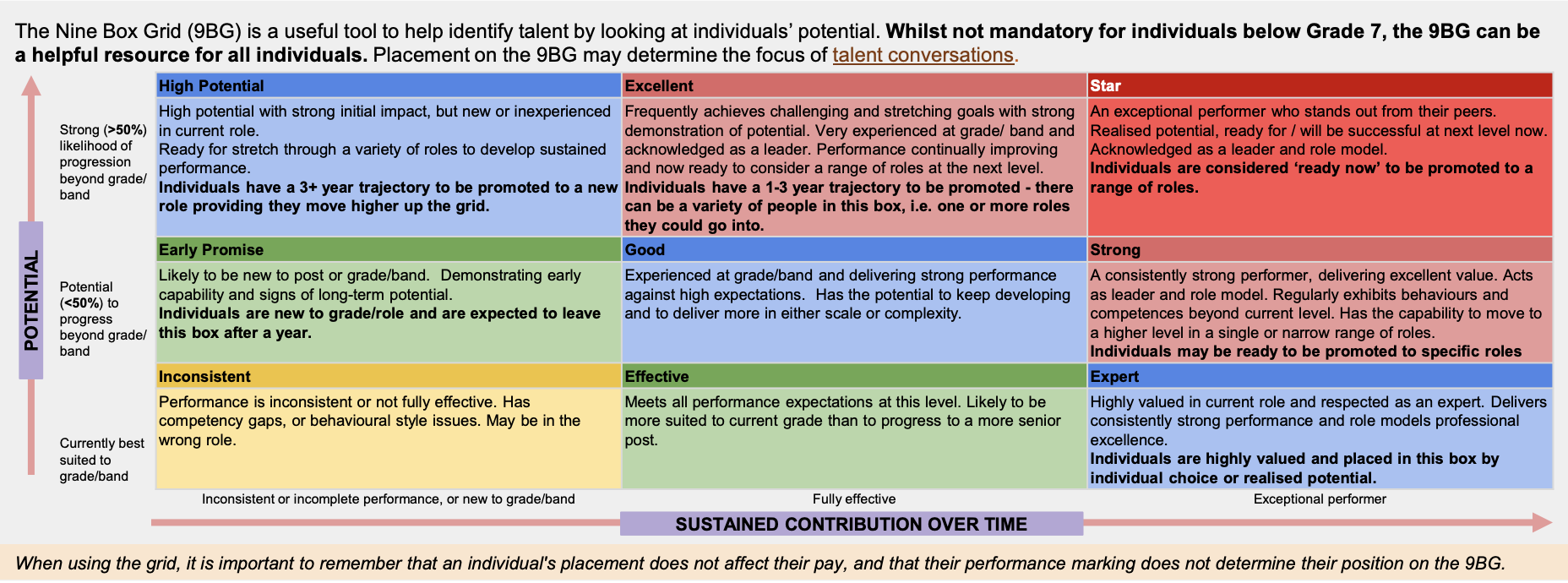

I first became aware of this self-explanatory Nine Box Grid in early 2023 although it may have been around for some time. I can see that it is meant to be helpful but:

- the allocation of individuals to one of nine boxes is likely to lead some 'interesting' if not acrimonious performance discussions, and

- such allocations run the serious risk of being self-fulfilling as they encourage or discourage, according to where staff are told they appear on this grid.