Rulers have always needed civil servants - and especially tax collectors. ("And all went to be taxed, every one into his own city.")

They also needed filing clerks!

"For all his flaws, King John was an assiduous administrator. He was very keen on filing, and it is the filing system that seems to have originated in his reign that formed the backbone of the record-keeping systems of English (and later British) royal government for centuries. They gradually evolved into the vast and varied collections of public records that are today in the safekeeping of The National Archives.

This is not to say that kings before John had never kept records. There is evidence that Anglo-Saxon kings had archives of their written documents, and we know that the 12th century Exchequer (the royal finance office) kept annual records of accounts called pipe rolls; the earliest surviving pipe roll (though not the earliest to be created) dates from 1130, and there is a nearly unbroken series from 1156 until the 19th century. 3 We should perhaps not be surprised that the desire to keep track of royal finances meant the Exchequer led the way in terms of record keeping!

But it seems that it was not until 1199, after the accession of King John, that the royal Chancery, the writing office of royal government, started systematically preserving the many hundreds of letters that it issued in the king’s name every year. The letters despatched from Chancery covered a great variety of subjects and were effectively the means used by royal government to get stuff done. They range from great solemn charters making grants in perpetuity to tiny writs covering the nitty gritty of local business."

Samuel Pepys is often spoken of as an early (1600s) civil servant, but Claire Tomalin's biography of Pepys makes it clear that there was then no civil service as we know it: no career structure and no entry exams - and if things went wrong , those held responsible were sometimes arrested and imprisoned.

Michael Coolican's No Tradesman and No Women - The Origins of the British Civil Service offers an excellent and often entertaining history of the UK Civil Service from Thomas Cromwell through to the present day. It includes, for instance, the fascinating story of the East India Company where the phrase ';civil servant' was first used. The company set up a training college in 1796 and this establishment eventually settled at Haileybury.

As the years passed, the activities of the East India Company became increasingly governmental, and intertwined with those of the British Government in London. Pressure grew to allow open competition for appointment by the Company, and this was important background to the parallel thinking that led to the Northcote-Trevelyan Report. Ironically, given modern concerns, the strongest pressure came from what Michale Coolican calls the Balliol Conspiracy - a small group intent on ensuring that Oxbridge graduates could in future work for the East India Company. Haileybury according closed in the late 1850s, to reopen a couple of years later as the 'public school' that we know today. Trevelyan himself did not want to give up his won powers of patronage but was forced to do so, including following an intervention by William Gladstone, whilst the 1854 Northcote Trevelyan Report was still in draft. Nevertheless, the report is now best known for establishing the rule that civil servants are appointed on merit and through open competition, rather than patronage.

The report is famously critical of the quality of the 1850s civil service and was, as a result, strongly attacked at the time by Heads of Departments and their staff, including one Anthony Trollope who had obtained his Post Office clerkship because one of his mother's friends was the daughter-in-law of the secretary of the Post Office. His semi-autobiographical novel The Three Clerks can be read as attacking promotion on merit.

Another ardent critic was The Treasury's Patronage Secretary William Hayter who was alleged to keep two half-wits on the payroll (known as 'Hayter's idiots') whose only function was to compete for promotion with Hayter's desired candidate, thus ensuring that the favoured man always secured the post.

Trevelyan was himself hardly committed to the virtues, such as effective competition for appointment and promotion, that eventually became embedded through the civil service. Indeed, Robert Lowe is probably due much more of the credit. It was his 1870 Order in Council that ensured that were only a small number of exemptions from competitive exams.

1854 also saw the publication of the Macaulay Report on the Indian Civil Service.

The Northcote Trevelyan reforms had been a reaction to widespread, nepotism, corruption and inefficiency. But they took a long time to become fully embedded in civil service culture - arguably until the early 1900s. Minister/civil service relations then reached 'glorious harmony' after World War 2, but it has been downhill ever since with politicians increasingly seeing civil servants as 'part of the problem', not 'part of the solution'. This is a particular feature of the early 2020s profoundly insecure government. Whether or not as a result of this, much of the current civil service lacks a culture of curiosity and challenge. (I would add that this is also because austerity-driven staff cuts, and the closure of the National School of Government, have led to striking reductions in training and thinking time.)

Here are some interesting documents which shed light on the organisation and culture of the civil service from the early1900s. Later developments are covered in detail in the Civil Service Reform section of this website.

- The 1918 Haldane Report recommended changes that had been shown to be necessary as a result of various problems that had arisen during the First World War. The relationship between civil servants and Ministers became one of mutual interdependence, with Ministers providing authority and officials providing expertise.

- There was an interesting Board of Inquiry Report published in 1928 concerning gambling in movements in foreign currencies which had been carried out by a Mr Gregory and a small number of other Foreign Office officials. Their activities had been brought to light by a court case involving a Mrs Dyne who was also part of the informal syndicate that engaged in the speculative transactions. The Board concluded (para 18) that none of the officials had used, or tried to use, any official information when deciding on their 'investments' but "a course of speculative transactions such as we have described above ought never to have been entered upon by any Civil Servant. Least of all ... by those to whom , from the nature of their work, the sensitiveness and suspicions of foreign countries with regard to such dealings in their currency cannot have been unfamiliar."

- The scandal (if that is not too strong a word) was known at that time as 'The Francs Case' - Francs being the French currency of the day.

- The officials concerned were disciplined but (at least) one of them - a Mr O'Malley - appealed against his forced resignation and was reinstated. He later became Sir Owen St Clair O'Malley, an Ambassador and the author of a famous mid-World War 2 report establishing Russian responsibility for the Katyn massacre.

- Historians might also be interested in Part III of the report which considers and dismisses concerns about Mr Gregory's involvement in the events surrounding the 1924 fake Zinoviev Letter.

- HM Treasury's 1949 Handbook for the New Civil Servant offers a superb insight into the culture and organisation of the post-war Civil Service. It in particular quotes paras 54 to 59 of the above-mentioned report as "the nearest things we have to a written "Civil Service Tradition" which "deserve careful study".

- The 1980 version of the above document is here.

- Cabinet Secretary Sir Edward Bridges' 1950 Portrait of a Profession "describe(s) the inhabitants of Whitehall in terms of the training and tradition, the outlook of mind, and aspirations which play so big a part in determining men's actions".

- The Civil Servant and His World - a young person's guide was published by Gollancz in 1966 and provides a rather more informal update to the 1949 Treasury handbook mentioned above. Follow these links to read:

Most, if not all, of the above documents assume (correctly) that the Civil Service was predominantly a male preserve until the 1960s. This began to change after the publication of the Kemp-Jones Report in 1971. But there had of course been a good number of impressive and ground-breaking female civil servants employed before then. The Women in the Civil Service section of this website has a lot more information about them and about the employment of women in the civil service through to the present day..

Richard Willis has written an interesting History of Civil Service Exams.

Boards, Ministries and Departments

Civil servants find themselves working within organisations whose names often seem to be lost in history. And, as so often in the UK constitution, there is no firm description which can help an outside observer predict an organisation's likely classification. In short, however,:

Boards were originally meant to indicate an authority composed of more than one person whose functions were mainly administrative and which met, deliberated and was not itself answerable to Parliament. The Board of Inland Revenue was one such, until it was subsumed into Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs.

Over time, Parliament decided to exert greater control over the more important of these organisations, and so imposed ministerial supervision - hence Ministries headed by a single politician, exclusively responsible to Parliament, and the most powerful and yet the most temporary element in the organisation. The Board of Agriculture and Fisheries, for instance, became the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF). Sometimes, however, organisations headed by ministers retained their old names - such as the Board of Trade, until it was subsumed into the Department of Trade and Industry in 1970. Even then, though, its Secretaries of State have sometimes preferred to be called President of the Board of Trade. Follow this link for a more detailed history of Presidents of the Board of Trade.

And then ... most Ministries, over time, became renamed Departments - presumably a more modern sounding designation. MAFF was eventually subsumed into the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. But, rather surprisingly, a new Ministry was created in 2007, the Ministry of Justice.

At and Around Offices

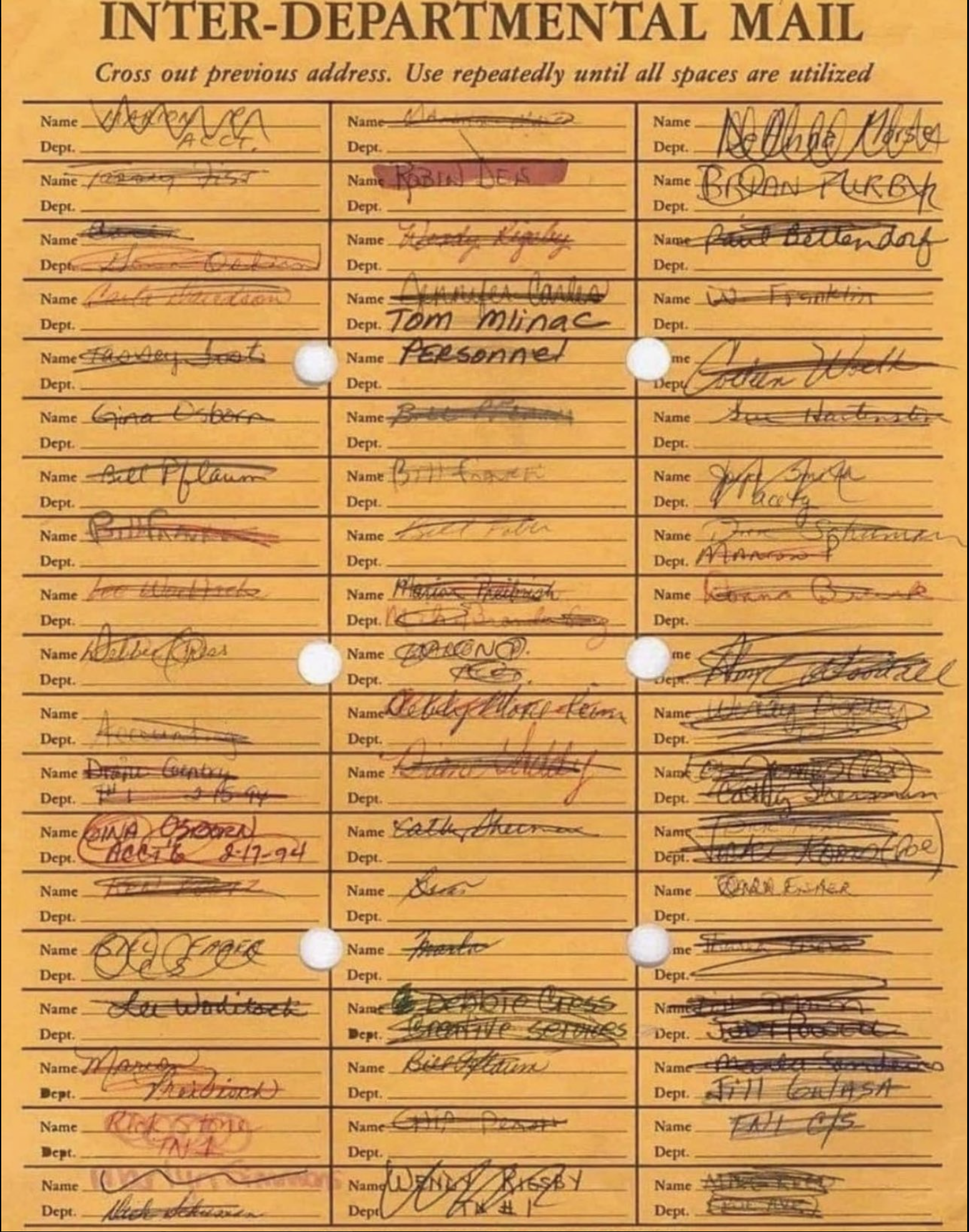

Internal envelopes such as this one saved paper as they facilitated the movement of papers around departments until superseded by email.